ST KILDA CEMETERY

260-288 DANDENONG ROAD ST KILDA EAST, PORT PHILLIP CITY

-

Add to tour

You must log in to do that.

-

Share

-

Shortlist place

You must log in to do that.

- Download report

Statement of Significance

What is significant?

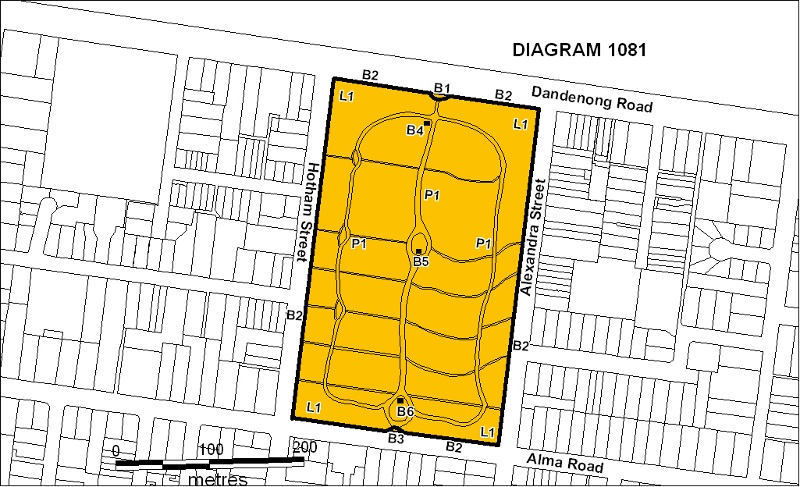

St Kilda General Cemetery, occupying a rectangular site of around 20 acres, is bounded by Dandenong Road, Hotham Street, Alma Road and Alexandra Road and includes over 51,000 burials. The earliest known record of St Kilda General Cemetery is a grid plan drawn by Robert Hoddle's assistant surveyor HB Foot in 1851. This plan provided separate sections for the Church of England, Catholic, Presbyterian, Wesleyan, Independent and Baptist denominations. The new cemetery had a capacity for 20,000 graves, with no allocation made for Jews, Chinese or Aborigines. By the time the cemetery opened on 9 June 1855, Hoddle's grid plan had been overlaid by a less formal system of winding and intersecting paths, inspired by the contemporary garden cemetery movement, which in turn drew on the Picturesque landscape tradition that was popular in England at this time and the writings of landscape designers such as John Claudius Loudon.

By 1900, there were no grave sites left according to the original plan and the cemetery was closed except to holders of burial rights. The Minister of Health agreed to reopen the cemetery in 1928 and a further 250 graves were offered for sale. Additional plots had been created by narrowing roads, and by appropriating pathways and ornamental reserves. The cemetery experienced degrees of decline and neglect throughout the twentieth century, the most extreme in the 1950s. By 1967, all grave sites had been sold and the cemetery was in crisis; about 50,900 burials had taken place since 1855 and only 700 graves remained to be used. The Necropolis Trust, Springvale, assumed responsibility of St Kilda Cemetery in 1968. St Kilda Cemetery was closed for burials in 1983, except for some remaining places in niche walls and the lawn cemetery.

The site is bounded by a red brick, stone and iron fence. The boundary fences on the west (Alexandra Street) and east (Hotham Street) are high with stone coping. The rear (Alma Road) and front (Dandenong Road) fences are lower, featuring a low brick wall with stone coping supporting iron palisades. The front and rear gates connect with a series of tall stone pillars designed in a Gothic style. The central entrance gates and immediate fence are set back from the roadway in an arc formation. Inside, is the Michaelis Lawn with niche walls and a memorial rose garden. The gate-lodge or sexton?s residence and office once stood at this location. This pair of nineteenth-century brick, slate-roofed buildings, designed in the Picturesque cottage orne style, were demolished by the Trust in the early 1970s.

The grounds are divided into bands of denominational sections, with Church of England to the east of the entrance followed by Catholic, Church of England, Wesleyan, Presbyterian, Independent, Baptist, Other Denominations, and Hebrew. The occasional iron denominational marker can be found in the grounds; a remnant marker, for example, survives in the Church of England B section.

A curving central roadway, which extends down the middle of the grounds, is broken by two circular islands that were once garden beds with rockeries. The rear island near the Alma Road gates now comprises Hebrew burials. The island near the middle of the cemetery retains its lawn and two Bhutan Cypresses, but also contains one prominent grave, that of airman and World War I hero, James Bennett (1894-1922). There are three shelters along the central axis, located at the front (west side of central roadway), middle (rear/south of Middle Island) and rear (front/north of Hebrew Island). All three are different but of similar interwar period construction, featuring timber and terracotta fabric. At least two were built in 1930. A series of red brick paths extend either side of the central roadway providing access to compartments. A ring road of gravel encircles the outer compartmental areas.

There is a large collection of monuments of fine workmanship or unusual design and construction, including rare cast iron and sandstone memorials and those built by prominent Melbourne sculptors, such as Jageurs & Son. Many graves have decorative iron fences or grave surrounds. There is also a large variation in funereal motifs, including some rare examples. Significant monuments include the Robb memorial with a seated woman in a colonnaded tomb; the Arts and Crafts Celtic Revival design memorials for Joseph Panton (1913) and Eleanor Panton (1896); the Anne W. Murray memorial (1875), an obelisk with ivy and gum leaves entwined around an anchor motif; the Captain Robert Russell Fullarton memorial (1895), a capstan with rope; cast iron memorials of the Klemm and McDonald families, 1870, 1877 and 1878; the fireman?s motifs on the memorial for James Kelly; the Macmeikan family memorial, a representation of a Scottish stone cairn surrounded by an iron fence in the form of a rustic vine; and the Art Deco style grave of Evelina Nathan, 1938.

Monuments to prominent individuals include Alfred Deakin, politician and Prime Minister (1856-1919); botanist Ferdinand von Mueller (1825-1896); Albert Jacka, (1893-1932) awarded the Victoria Cross; architect William Pitt (1855-1918); Sir Frederick Sargood (1834-1903); photographer Nicholas Caire (1837-1918); early pastoralist Janet Templeton, died 1857; businessman and philanthropist Alfred Felton (1831-1904); writer Tilly Aston (1873-1947); and three 1840 fever victims from the emigrant ship Glen Huntly (1898), reburied at St Kilda in 1898. The cemetery is also notable for including the graves of a number of Victorian Premiers including the first ? William Clark Haines: George Briscoe Kerferd; Sir Bryan O?Loghlen; the politician, temperance leader and land boomer Sir James Munro; and Sir George Turner (who was also the first Federal Treasurer).

St Kilda Cemetery contains a varied collection of plants that are typical of nineteenth-century cemetery planting, although most of the trees date from the twentieth century. The cemetery landscape has undergone considerable changes with a number of trees removed.

How is it significant?

St Kilda Cemetery is of aesthetic, architectural, historical, and social significance to the State of Victoria.

Why is it significant?

St Kilda Cemetery, which opened on 9 June 1855, has historical significance as one of Victoria?s oldest public cemeteries, and for its remarkable collection of monuments and memorials. The oldest human remains in the cemetery are the re-interred remains of three men from the fever ship Glen Huntly, which were first buried at Point Ormond (Elwood) in April 1840.

St Kilda Cemetery is of historical and aesthetic significance for its rich and remarkable collection of monuments dating from the 1850s onwards, which demonstrate changing customs and attitudes associated with the commemoration of death. Many monuments are notable for their fine or unusual design. The collection charts the lives and deaths of many ordinary as well as prominent Victorians. The large number of graves to notable Victorians reflects the development of the south-eastern suburbs as a relatively prosperous area in the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries.

St Kilda Cemetery has aesthetic and architectural significance as an early and sophisticated example in Victoria of cemetery planning that was inspired by Picturesque notions of beauty. The influence of the garden cemetery movement is particularly evident in the layout, curving paths and roadways, plantings, ornamental fence and gates, shelters, as well as the memorials which form a major visual element of the cemetery landscape.

St Kilda Cemetery is of aesthetic significance for its landscape with its collection of significant trees including several large and outstanding Bhutan cypress (Cupressus torulosa); three large Camphor Laurels (Cinnamomum camphora); Flowering Gum (Corymbia ficifolia); a large London Plane (Platanus x acerifolia); Himalayan Cedar (Cedrus deodara); an Irish Strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo); Chinese Windmill Palm (Trachycarpus fortunei); a Velvet Ash (Fraxinus velutina), an unusual planting for a cemetery; and a Western Red Cedar (Thuja plicata). A major landscape feature is a hedge of Golden Privet (Ligustrum ovalifolium 'Aureum') planted behind the palisade fence along Dandenong Road and Alma Road.

-

-

ST KILDA CEMETERY - History

This report was prepared by Michele Summerton with assistance from Sera Jane Peters and Pearl Donald, of Friends of St Kilda Cemetery Inc. Heritage Victoria officers and members of the Friends Group, Geoff Austin and John Hawker were also consulted.

Contextual History

Planning for the disposal of the dead as well as attitudes to death were major concerns of Britain’s Victorian Age and accompanied the century’s legacy of great sanitary reforms. With phenomenal shifts in the population from rural to town and city concentrations, Britain’s urban graveyards quickly became overcrowded leading to consequences injurious to health and offensive to decency. As reaction to the gruesome horrors of urban graveyards set in, the movement towards establishing large metropolitan garden cemeteries gained momentum, and the cemetery as we know it became a phenomenon of cities and towns.Other factors were also propelling the establishment of cemeteries. The nineteenth century was an age of increasing dissent towards the established (Church of England) church and the rise of other denominations. Those who were not Anglicans felt they should not have to be buried in Church of England parish churchyards or burial grounds attached to churches. The new cemeteries provided for all religious persuasions, however many still were divided into consecrated and unconsecrated grounds, some with their own Anglican, Roman Catholic and Nonconformist chapels.

The patterns that shaped Britain’s emergent middle-class life also shaped its commemoration in death. The values of individualism and bourgeois respectability associated with everyday life in the nineteenth century metropolis also found expression in a new funeral culture that accompanied the advent of cemeteries. Undertaking became a commercial enterprise, with a decent burial demanding an elaborate rite of passage for the rich or for the less wealthy ‘a good send off’, culminating in the committal of the body at a graveside burial. Funerary monuments proliferated; built to stand in perpetuity, they defined one’s social place but also allowed those of uncertain social position to posthumously advertise their success. Monuments were like a sculpture gallery, a lesson in styles and taste and many of the more spectacular examples were architecturally designed.

The choicest jobs for architects however were for designs of complete cemeteries. Ensembles of Gothic or Renaissance chapels, handsome gate lodges and monumental entrance gates became the norm for new cemeteries, with the whole providing cleverly designed paths within an enclosed ‘world where nature, architecture, art, and landscape gardening combined in an illusion of quiet, peaceful, permanent rest for the middle-class dead’.. Many of the new cemeteries in the English provinces were an attempt at civic improvement by private enterprise often much needed in towns of rapid industrial development.

Père-Lachaise, Glasgow Necropolis, Kensal Green, Highgate & Abney Park cemeteries

The prototype for the nineteenth century cemetery as landscaped funerary garden emerged in 1804 in Père-Lachaise Cemetery, established in Paris on a hill to the east of the city. Instead of a church or malodorous churchyard burial, here one could be fashionably interred in ‘a terrestrial Paradise, an Elysium, and an Arcady, where the enchantments of landscape-gardening, nature, art, and architecture alleviated the gloom of the grave’. Owing much to the English landscaped garden of the eighteenth century, Père-Lachaise soon became world-famous with its influence shaping an entirely new funerary culture in the western world. Plans for a spectacular Scottish version of the cemetery followed in 1831, with a proposal for converting a rocky hillside park into an ornamental cemetery, to be known as the Glasgow Necropolis.Improving the system of burial in the London metropolis began to gain momentum by the late 1820s and early 1830s generating a great deal of discussion in publications, meetings and parliamentary debate. Several of the more influential promoters formed the General Cemetery Company, and in July 1831 the purchase of 32 hectares (77 acres) of land at Kensal Green was approved. The General Cemetery of All Souls at Kensal Green opened in 1833, and in the same year classical designs were prepared for two chapels, one for Anglicans (built 1836-37), one for Dissenters (built 1833-34), a colonnade over catacombs, and an entrance gate and lodge (both 1833-34). Underneath the chapels there were brick catacombs comprising shelves for the placement of coffins. Planted and laid out in walks, with parterres and borders of flowers, Kensal Green with its attractive grounds and handsome Greek buildings soon proved popular. Its fashionable status elevated by the graves of several aristocrats, members of the royal family and monuments of rare or imposing architectural quality.

The huge success of Kensal Green inspired the formation of more commercial cemeteries in rapid succession in provinces like Leeds and Birmingham, as well as around London. Stephen Geary (1797-1854) architect, entrepreneur, and member of the London Cemetery Company, is associated with the founding of the Cemeteries of Highgate, Nunhead, Peckham, Westminster, Gravesend and Brighton. He may have undertaken the initial surveys and plans for north London’s Cemetery of St James, Highgate, as well as designs for the spectacular ring of Egyptianising catacombs around an existing Cedar of Lebanon, the perimeter walls and the two chapels on either side of the Tudor gate-house. Like Kensal Green, it had two chapels, one for Anglicans, the other for Dissenters with parts of the cemetery ground reserved for unconsecrated and consecrated burials (the Anglican section was consecrated on 20 May 1839). Highgate ‘became the definitive cemetery of the London bourgeoisie’.

The Abney Park Cemetery of 32 acres was founded in 1840 in London. Established by the Abney Park Cemetery Company, it differed from its predecessors by being open to all religions, with no separations into denominational divisions and with no consecration of the burial ground ever occurring. The structures included an oecumenical Gothic Chapel built in brick with stone dressings, small catacomb in an underground chamber separated from the Chapel, and Portland stone Egyptian Revival entrance-gates and lodges. The grounds inherited a landscape of lush planting which was retained and enhanced by adding some 2,500 varieties of trees and shrubs and over 1000 roses, forming an arboretum and rosarium, with many of the species labelled. The Cemetery catered for the more modest burials of proletariats and accordingly lacks the grand monuments of Highgate or Kensal Green. It was taken over by the London Borough of Hackney Council in 1978.

History of St Kilda Cemetery

A plan drawn by Robert Hoddle’s assistant surveyor H. B. Foot, on 20 November 1851 is the earliest known record of St Kilda Cemetery. It shows the allocation of land divided into a grid pattern providing the Anglicans and Roman Catholics with four acres each and two acres each to the Presbyterians, Wesleyans, Independents and Baptists. Another four acres were reserved at the rear for an extension. The plan was laid before the Legislative Council and approved in December 1851. The specified capacity of the new cemetery was for 20,000 graves. No allocation was made for Jews, Chinese or Aborigines. The plan was approved on 1 December 1851, and permission was granted from the Colonial Secretary for the proposed cemetery site early in 1853. The cemetery did not open until 9 June 1855, although the burial registers indicate that there had been a burial in the Baptist section earlier that year. By this stage, Hoddle’s grid plan had been overlaid by a less formal system of paths, a scheme more in tune with the contemporary garden cemeteries movement and picturesque notions of beauty popular in England at this time. Melbourne General Cemetery, which opened in 1853 had led the way locally in advancing this aesthetic in its layout and design and choice of plantings, structures and furnishings, and many new cemeteries set up in the new Colony of Victoria over the next decade were influenced by these ideas.In the meantime an Act for the Establishment and Management of Cemeteries in the Colony of Victoria had been passed by the Victorian government in 1854. This formed the basis of the state’s cemetery administration as it is organised today. It provided the government with the power to appoint and remove trustees and to lend or pay money for the establishment and management of cemeteries. Trustees were charged with the responsibility to keep accounts and statements, erect structures and plant trees, and impose management rules and regulations. They were to provide ministers of religion access to the cemetery and allow denominations to build mortuary chapels, and trustees also had the power to disallow inappropriate monuments or such structures. The Public Health Act and the Municipal Institutions Establishment Act were also passed the same year, 1854. Their broad ranging public powers also vested local councils with responsibility for the management and trusteeship of public cemeteries. Eleven trustees had been appointed for St Kilda Cemetery early in 1855, two representing each of the municipalities of Prahran and St Kilda, and one each representing the denominations. The first ‘rules and regulations’ were published in the Government Gazette during 1856.

Office and residence

A photo of the entrance to St Kilda Cemetery taken in 1866 shows the rules and regulations exhibited on two notice boards either side of the gates. Here the fence is of timber paling construction, with the gates and pillars being less imposing examples of those there today. Just inside the entrance stands a fine pair of brick, slate-roofed buildings. Designed in the Picturesque cottage orne style they feature ornately carved finials and barge-boards, windows with hooded drip moulds, decorative gable vents and a gabled entrance porch. Their simple design and concern for the Picturesque liken them to similar examples popularised by architectural pattern books, such as the designs promoted by J C Loudon and John Starforth. The St Kilda buildings would seem to comprise an office as well as a sexton’s residence, the latter being less common in Victoria and usually the preserve of elaborate cemeteries. British cemeteries usually included a residence for the sexton or his superintendent, and were likely to have imposing, arched and walled entrances with flanking gate lodges. They were frequently built in Tudor, Egyptian, Classical or Gothic style to enhance the ornamental qualities of the cemetery.The gatekeeper’s lodge or sexton’s office became a vital component of the nineteenth century colonial cemetery, and ornate or rudimentary examples went up in cemeteries in colonial Victoria. It was here that the sexton maintained a plan of the burial plots and dealt with other matters pertaining to the cemetery’s day to day function. A temporary office-cum-lodge was constructed at the Melbourne General in the 1850s and replaced by more ornate Gothic examples, along with a residence in 1867 and 1869. Castlemaine erected a small office of bichrome brick construction between 1858 and 1859, and Bendigo’s Back Creek Cemetery built a slate roofed, stone lodge, which was completed by March 1858. At around the same time, the White Hills Cemetery, also at Bendigo, built a brick lodge (since demolished). Maldon Cemetery constructed a brick office and residence at the entrance in 1866, and Boroondara Cemetery (Kew) commenced a brick lodge and residence in 1860, later extended by architect Albert Purchas.

Some of the earlier lodges/offices were replaced or extended, but most have not survived. A photo taken in about 1890 indicates that St Kilda Cemetery had added an elegant Romanesque bell tower over the gabled entrance porch to the gate-lodge some time before this date as well as the fine set of Gothic gate pillars and dwarf brick and palisade iron fence. Another photo held by the State Library of Victoria indicates that the steep slate cap on the bell tower had been removed by 1939. Many residences and/or lodges like those at St Kilda Cemetery eventually fell into neglect and were demolished to provide for more burial space as cemeteries became overcrowded. St Kilda lost its residence and lodge in about 1969-70.

Agitation against the cemetery

Neighbouring landowners did not welcome the addition of a cemetery to their suburban environs. Throughout the 1860s East St Kilda residents tried to have the cemetery closed due to claims that its sandy foundations were allowing pollution of underground streams and the value of their properties was depreciating. They also moved to have the cemetery limited to the use of those then possessing burial deeds, fearing that the cemetery would become overcrowded and offensive to public hygiene. In 1865 a ‘memorial’, presented to the President of the Board of Land and Works by an influential deputation claiming to represent the views of ‘a considerable proportion of the inhabitants of St Kilda’, advocated that a new cemetery be opened near Caulfied racecourse. The cemetery trustees opposed the idea, mainly for financial reasons. They had outlayed £5300 on buildings, gardens and other improvements, and the total investment including monuments amounted to £14,210. Since opening in 1855 the cemetery had sold 1373 graves, of which 944 were private and 430 public, with a total of 2342 persons buried there. Mr Grant, representing the government supported an alternative site at Caulfield, however the move failed, and grave sales continued, along with press correspondence about the unsatisfactory conditions at St Kilda Cemetery.Although the actions to move the cemetery were thwarted by the Council and cemetery trustees, local residents did gain a concession; those living in Mort Street successfully petitioned to have their street renamed Alexandra Street in 1874. By now the cemetery occupied its present block bounded by Dandenong Road, Alexandra Street, Alma Road and Hotham Street. The original site for the cemetery is believed to have covered about 60 acres, extending from Hotham Street to Orrong Road. Disquiet about the cemetery broke out again, in September 1876 when R. M. Smith, MP for St Kilda proposed that the cemetery regulations be altered to allow for the transfer of burial sites between denominations, as burial spaces for the larger religious faiths were running out. Many argued that this was just delaying the inevitability of the cemetery’s need to close. Thomas Bent, MP for Brighton even suggested that the valuable cemetery land be sold and the bodies removed for reburial elsewhere. Another MP, J. B. Crews of South Bourke opposed Smith’s plan of cramming the grounds with plots. Arguing from a garden cemetery point of view he asserted that the cemetery was ‘a place of resort, if not of recreation, for the living’. When the government purchased land in 1878 at Spring Vale for a much larger cemetery, it fuelled speculation that St Kilda’s closure was imminent, with some newspapers predicting that the cemetery would close from February 1879.

Beautification works

Many of the larger 1850s cemeteries, such as Melbourne General, Ballarat Old Cemetery, Geelong’s Eastern Cemetery, Bendigo Public Cemetery (formerly Back Creek Cemetery), White Hills Cemetery as well as some of the smaller cemeteries like Williamstown maintained a number of beautification projects throughout the nineteenth century. These included the building of ornamental boundary fences, floral borders, rockeries and rotundas as well as an occasional fountain. St Kilda’s new fence, gates and pillars went up sometime between the 1870s and 1890s, the same years in which Bendigo and Melbourne General completed their fences in stages. All adopted a dwarf fence of stone or brick with solid pillars and iron railing. St Kilda’s ecclesiastical or Gothic-inspired design was probably built in stages. The style was a fashionable choice of the period, enhancing the ornamental qualities of the cemetery as well as the wide Dandenong Road boulevard. Rockeries were popular in the 1890s and a photo post card held by the State Library reveals that such arrangements existed along the main walks at St Kilda Cemetery. Like Williamstown Cemetery and Ballarat Old (1856) and Ballarat New (1867) cemeteries, St Kilda also had an ornamental fountain with two bowls, although today no evidence of it or the rockeries remains.Further complaints: the 20th century

Despite repeated moves to close the cemetery, it continued to function. The matter of closure and overcrowding erupted from time to time, but always there were counter pressures. By 1900, after 20,329 burials, there were no further grave sites remaining according to the original plan. An Order-in-Council of April 1899 had directed that the cemetery finally close, with no more burials except for those who already held deeds or right of burial certificates or for those who had purchased allotments before the 31 December 1900. The latter condition precipitated an immediate selling off of broad floral borders and beds.A Board of Inquiry into the cemetery, held in 1907, investigated complaints of trafficking in cancelled and suspended burial rights. There were also complaints that trustees and employees were purchasing rights of burial at lower rates than the gazetted scale of fees, and that trustees were unfairly competing with grave decorators, monumental masons and others. In 1909 trustee secretary J. H. Thomas still maintained that there was room for an extra 15,000 interments even though the cemetery was at breaking point with 33,113 burials. In 1913 there were further complaints that undertakers were ‘trafficking’ in graves, purchasing sites for £3 and allegedly reselling them for £15 to £18. There were rumours that this was also going on at Melbourne General as well. J. H. Thomas responding for the St Kilda trustees denied such wrongdoing, but it was a particularly sensitive issue and Thomas was dismissed.

The crack down on grave selling had the unfortunate consequence of drying up income to maintain the grounds, which rapidly deteriorated. As a result pressure mounted to reopen the cemetery. Closure was amended to allow for the authorised sale of a small number of plots in 1923 and again in 1928 when a further 250 were released. These were mainly limited to stretches of old roadway and pathways. The Minister for Health reminded the cemetery of its obligations to maintain and beautify the grounds now that funds were apparently available for such works.

Two shelter sheds were constructed in 1930 and an old shelter removed. A section of the front entrance area was concreted, many paths were bricked and a number of staff recruited for maintenance works. By the following year, 1931, the number of burials reached 39,761. Improvements continued, and in 1932 a newly appointed curator established a nursery and a conservatory. Space was reclaimed where old buildings once stood, and the secretary’s office, known as the lodge, was converted into two self-contained flats, one being occupied by the curator.

Despite these initiatives, press criticism of unsatisfactory maintenance standards and neglected graves persisted, particularly from the 1930s. Further allegations surfaced on the trafficking of grave sites, again an activity that was not confined to the St Kilda Cemetery. In 1933 all the secretaries of Public Cemeteries were asked to comment on the rumour that undertakers were still profiteering from purchasing graves from cemetery trusts. In 1935 the trustees were accused of having exceeded the number of 250 plots allowed by the government in 1928, and had sold another 700 by closing off too many pathways and reducing the width of roads. This was an offence against the Cemeteries Act, but the Trust argued that the cemetery had insufficient funds to maintain the grounds.

The last five grave sites were sold in 1966, and on 1 April 1967, the trustees of The Necropolis, Springvale, assumed responsibility for St Kilda Cemetery pending a government decision on its future. In the course of parliamentary debate on the Cemeteries Bill (St Kilda Public Cemetery) in November 1967 it was stated that all possible grave sites had been sold and that about 50,900 burials had occurred since 1855, and some 700 burials rights were still current. Without income from the sale of graves and with financial reserves still inadequate for the upkeep of the grounds and the municipal council unwilling to accept any responsibility for their maintenance, it decided that the cemetery should be taken over by The Necropolis Trust, Springvale. In 1969 approval was give for the Trust to demolish the two existing gate-lodge buildings inside the main entrance to provide space for a lawn cemetery, rose garden, niche walls (columbaria) and a new caretaker’s office. Other structures to be demolished included maintenance buildings and the fountain to the left of the gates.

In September 1983 the Governor-in-Council approved an order discontinuing further burials in the cemetery except where prior burial rights existed. This effectively closed the cemetery by government order. A limited number of memorial wall niches and rose garden positions remain available.

The Friends of St Kilda Cemetery Inc. was established in 1998 by a group of people with a shared interest in the history and conservation of the cemetery. The group conducts tours of the cemetery and has a web site and newsletter. It has recently published a collection of stories about people buried in St Kilda Cemetery (Meyer Eidelson, Nation Builders: Great Lives & Stories from St Kilda General Cemetery, published by Friends of St Kilda General Cemetery, 2001).

An Overview of the People Buried in St Kilda Cemetery

Some of the oldest remains in St Kilda Cemetery come from exhumed graves. Some remains were brought from the old Melbourne Cemetery between 1920 and 1922. In 1898 the remains of the three Glen Huntly pioneers were removed from Point Ormond (Red Bluff) due to the sea encroaching on the graves. Passengers on the Scottish ship Glen Huntly, John Craig, James Mathers and George Armstrong, had died of fever in 1840 at Melbourne’s first quarantine station at Red Bluff. The Board of Public Health removed the remains to the St Kilda Cemetery on 27 August 1898 and a monument was unveiled on 16 April 1899.Charlotte Green was the first recorded burial in the cemetery on 2 May 1855 in the Baptist section. The cemetery’s small collection of 1850s memorials comprises tablet-style headstones carved from sandstone. A good example stands on the grave of Janet Templeton who died in January 1857 aged 72 years. Janet, whose biographical details are included in the ADB (under William Forlonge 1811-1890), led an enterprising life as a pastoralist before finally settling in Melbourne. The headstone has survived its 145 years with surprising integrity, although the base is beginning to erode and cracks are starting to appear down the side. Other pastoralists buried in the cemetery include the Manifolds (Sir Walter 1849-1921, and Thomas 1809-1875 and families; ADB) and the King family including John (1820-1895), William (1821-1910) and Arthur (1827-1899; all ADB). Some of the Armytage family of Como fame are buried here, as are the Sargoods of Rippon Lea.

In the 1860s John Owens (1809-1866; ADB) was buried in the cemetery. A medical practitioner, goldfields leader and advocate of popular rights, Owens agitated on behalf of the Bendigo mining community for abolition of the licence fee, became a member of the Legislative Council and Assembly and served on eight select committees. Former Premier of Victoria, William Haines (1810-1866; ADB), also practised medicine initially. He is buried in the Anglican section. Another politician as well as judge and welfare advocate Edward Wise (1818-1865; ADB) of NSW died suddenly when visiting Melbourne and was buried in the cemetery. Several prominent politicians, judges, barristers and administrators are buried here, including gold commissioner and politician William Anderson (1829-1882; ADB), politician and solicitor Norman Bayles (1865-1946; ADB), barrister and sportsman Walter Coldham (1860-1908; ADB), judge and politician Thomas Fellows (1822-1878; ADB), civic administrator and energetic Melbourne town clerk Edmund Fitzgibbon (1825-1905; ADB), Chief Harbour Master Capt Robert Fullarton (1829-1895; ADB), judge of the Supreme Court, federationist and Premier George Kerferd (1831-1889; ADB), politician and businessman Sir James Lorimer (1831-1889; ADB), barrister and federationist Sir Edward Mitchell (1855-1941; ADB), businessman, politician and temperance leader James Munro (1832-1908; ADB), goldfields commisioner, sheriff and Eureka confrontationist Robert Rede (1815-1904; ADB), Premier and first federal Treasurer Sir George Turner (1851-1916; ADB) and politician and Prime Minister Alfred Deakin (1856-1919; ADB). The grave of Alfred and Pattie Deakin is surprisingly humble and unpretentious for a former Prime Minister, but it befits Deakin’s spiritualist bent. The grave is located in the Baptist section near von Mueller’s columnar monument.

Many people who moved in Melbourne’s artistic and intellectual circles are buried in St Kilda Cemetery. These include artists Hugh Ramsay (1877-1906; ADB), Elizabeth Parsons (1831-?), James Quinn (1869-1951; ADB), Oswald Campbell (1820-1887; ADB), Henricus van den Houten (1801-?); Ernest Moffitt (1871-1899; ADB); photographer Nicholas Caire (1837-1918; ADB); architects Nathaniel Billing (1821-1910), Charles Cowper (?), Thomas Crouch (1832-1889), Kingsley A. Henderson (1883-1942; ADB), Arthur Ebden Johnson (d.1895, aged 74), Arthur Peck (?), William Pitt (1855-1918), Sydney Smith (?), Francis White (1819-1888; ADB), Nahum Barnet (?) and Ernest Willis (1867-1947; ADB). Writers include Edward Curr (1820-1889; ADB), Tilly Aston (1873-1947; ADB), Janet Mitchell (1896-1957; ADB), and historians include John Shillinglaw (1831-1905; ADB) and Henry Gyles Turner (1831-1920; ADB). Overbearing bureaucrat, agnostic, mining engineer and former chairman of the Board for the Protection of Aborigines, Robert Brough Smyth (1830-1899; ADB) was buried in the cemetery. There is noted organ builder George Fincham (1828-1910; ADB), anarchist bookseller David Andrade (1859-1928; ADB), well known bookseller and publisher George Robertson (1825-1898; ADB), as well as bookseller and publisher F. F. Bailiere (1838-1881) who died at the age of 43 as a result of an accident on the Hobson’s Bay Railway.

Businessmen and merchants include Herbert R. Brookes (1867-1963; ADB) and wife Ivy Brookes, Deakin’s eldest daughter (1883-1970), biscuit manufacturer Adolph Brockoff, businessman and art benefactor Alfred Felton (1831-1904; ADB), Frederick Grimwade (1840-1910; ADB), merchant and tanner Moritz Michaelis (1820-1902; ADB) and Sir Frederick Sargood (1834-1903; ADB).

Religious identities include Rabbi Jacob Danglow (1880-1962; ADB), Anglican Bishop John Hart (1866-1952; ADB), clergyman and controversialist John Rentoul (1846-1926; ADB) and Anglican clergyman Horace Tucker (1849-1911; ADB). The grave of Mary McKillop’s sister, Annie is marked by a large granite Celtic cross which dominates the cemetery’s north-west corner.

Scientists and medics include horticulturalist George Brunning (1830-1893; ADB), mariner George Calder (1839-1903; ADB), ornithologist Archibald Campbell (1853-1929; ADB), pharmacist Henry Francis (1830-1905), botanist Ferdinand von Mueller (1825-1896; ADB) and doctor Mary Page Stone (1865-1910; ADB).

Heroes and social notables include tennis player Sir Norman (1877-1968) and Dame Mabel Brookes (both ADB), Boer War soldier Sir John Hoad (1856-1911; ADB), WW1 hero Capt Albert Jacka (1893-1932; ADB) and airman and WW1 hero James Bennett (1894-1922; ADB).

A list comprising these burials and more is attached as an appendix to this report.

Memorials

The cemetery has a remarkable collection of memorials from the 1850s onwards demonstrating the humble to the elaborate in customs and attitudes associated with the commemoration of death. Two unusual memorials are the large headstones standing on the graves of Eleanor Panton who died in 1896 and her husband Joseph, goldfields commissioner 1852-58 and first metropolitan Police Magistrate of Melbourne, who died in 1913. The unique headstones are remarkable for their splendid Arts and Crafts Celtic Revival designs. The grave of architect Arthur Ebden Johnson who died in 1895 and his wife Laura displays a further example of Arts and Crafts design. The white marble memorial is chest or coffin shaped with a cross formed into the top. The metal lettering is in an Arts and Crafts style script. A copper wreath is appended to one end of the chest and the whole is surrounded by an intricately detailed low copper fence.One of the most imposing memorials is that to Ferdinand von Mueller (d.1896). Although the design of pedestal and column with draped urn is conventional for late nineteenth century monuments, this example is one of the tallest of its type. Not far from this monument and also dating from the late nineteenth century is the grave of Charles Nyulasy, his wife Sarah and their son Arthur. The well-crafted marble monument displays an interesting combination of funerary symbolism; an upward pointing hand clasping flowers, a crown and a radiating cross. Another well-crafted marble monument was made for Captain Robert Fullarton (1829-1895), former naval officer and Chief Harbour Master of Victoria. The monument takes the form of a wharf bollard with rope wound around it and a wreath draped over one side. It stands on a bluestone base and is surrounded by a decorative cast iron fence. Another fitting tribute to an identity is the iron fence designed to resemble taps and hoses, surrounding the grave of fire officer James Kelly (see Iron Grave Surrounds).

Near the cemetery entrance it is hard to miss the imposing portico containing the seated classical figure of a woman. This is the La Barte/Robb memorial. Another allegorical figure of a woman can be found on the grave of Frank Williams who died in 1919 aged 23. The mourning woman forms part of the grave’s headstone. An excellent example of 1930s funerary design is the Art Deco style grave of Evelina Nathan and her husband Robert. The striking black and grey granite memorial is streamlined with curved and tapered shapes and geometric detailing.

Iron Memorials

St Kilda Cemetery has a very good collection of iron memorials. This type of memorial is relatively rare in Victoria, with even the largest cemeteries in the State tending to include just a few examples. St Kilda would appear to have the largest number in Victoria.Cast iron grave markers were an innovation in the early nineteenth century and often took the form of headstone shapes but were usually of more modest dimensions. Mass-produced, they were made in a mould, with raised designs and lettering, and in a range of ornamental designs sometimes with openwork patterns. Metal grave markers were cheaper than marble or granite markers, and could be more elaborate in detail than stone would allow, and as stated above could be mass-produced. Some of the examples in Victoria were imported from Scotland where they were more commonly used. They were also used in America. Glasgow's Necropolis cemetery has huge cast iron monuments designed by George Smith and Co from 1870, the period from when those in Victoria are fabricated. Many survive in poor condition due to rust. They are also easy to uproot and steal.

St Kilda Cemetery’s Klemm and McDonald family iron memorials are exceptional for their size and unusual design. The three tall iron crosses (1870, 1877, 1878) are suggestive of the American iron cross markers on the graves of German immigrants who settled in Dakota. No comparable metal markers have been identified in Australian cemeteries, including cemeteries in the German settlement towns of the Barossa Valley. A fourth iron marker in the family plot is more conventional with a low headstone shape, although the Scottish references in the detail are interesting. Other iron markers in the cemetery include the floral-patterned, round-headed memorial to Richard McDonnell who died in 1877 aged 27; and the neoclassical-inspired, round-headed memorial erected by the Glaswegian parents of William Turner Russell, who died in 1886 at the age of 22 in the Albert Hospital Melbourne after an accident. The latter memorial is now detached from its base and is in danger of being removed from the cemetery.

Iron Grave Surrounds

St Kilda Cemetery displays a rich collection of ornamental cast iron grave surrounds. Various design phases in the use of cast iron ware for funerary purposes are demonstrated from simple hooped surrounds of the 1860s to the elaborate work of the late Victorian period. Some outstanding examples include the rustic iron surround of the Macmeikan family grave, which resembles a fence made from knobby tree branches or a hoary vine. Information on the memorial indicates that it was made by Chambers & Clutton of Lonsdale Street, Melbourne. The gate is broken and the ironwork is rusting. The monument inside the fence is equally remarkable being of granite roughly hewn to resemble a pile of boulders. Just discernible on the surface are postcard shaped inscriptions carved into the front and back of the monument, the whole resting on a bluestone pedestal and plinth. Another remarkable example of ironwork can be seen in the wonderfully ornate fence surrounding the Smith family grave combining Greek, Gothic and late nineteenth century aesthetic motifs. The detail is outstanding and the surround is generally in sound condition but for rusting and minor wear and tear. An unusual fence surrounds the grave of late nineteenth century fireman James Kelly. Its iron railings resemble hoses and nozzles, with sturdy taps and fireman emblemata at the corners.Plantings

An early photo of St Kilda Cemetery held by The Necropolis and dated 1866 indicates that fine examples of mature native trees (perhaps Red River Gums) still stood throughout the cemetery at this time. Over the years they were cleared to make way for burials and exotic plantings, many of which have in turn been removed as they became senescent or caused damage to graves. A few large stumps remain.

REFERENCES

Australian Dictionary of Biography, ADB CD-ROM version, Melbourne University Press, 1996 (various entries).

Clark, Laurel, ‘F.F. Bailliere Book Seller To The University Of Melbourne’, in The University of Melbourne Library Journal, December 2000, pp 13-15, 24-25.

Chambers, Don, City of the Dead: A History of The Necropolis, Springvale, Hyland House, Flemington, 2001.

Curl, James Stevens, The Victorian Celebration of Death, Sutton Publishing, Phoenix Mill, 2000 (2001).

Eidelson, Meyer, Nation Builders: Great Lives and Stories from St Kilda General Cemetery, Friends of St Kilda Cemetery Inc., St Kilda, 2001.

Friends of St Kilda Cemetery Inc. website: http://home.vicnet.net.au/~foskc

Heritage Victoria, file ‘St Kilda Cemetery’.

Heritage Victoria. Heritage assessment of Williamstown Cemetery by M. Summerton.

State Library of Victoria Picture Collection.

U.S. Department of the Interior, National Parks Service, National Register Bulletin, 41, Guidelines For Evaluating and Registering Cemeteries and Burial Places, United States Government Printing Office, 1995.

Victoria. Department of Human Services. Cemeteries Section. St Kilda Cemetery File.

Willsher, Betty, Understanding Scottish Graveyards (details not noted. This publication is held by SLV).

ST KILDA CEMETERY - Permit Exemptions

General Exemptions:General exemptions apply to all places and objects included in the Victorian Heritage Register (VHR). General exemptions have been designed to allow everyday activities, maintenance and changes to your property, which don’t harm its cultural heritage significance, to proceed without the need to obtain approvals under the Heritage Act 2017.Places of worship: In some circumstances, you can alter a place of worship to accommodate religious practices without a permit, but you must notify the Executive Director of Heritage Victoria before you start the works or activities at least 20 business days before the works or activities are to commence.Subdivision/consolidation: Permit exemptions exist for some subdivisions and consolidations. If the subdivision or consolidation is in accordance with a planning permit granted under Part 4 of the Planning and Environment Act 1987 and the application for the planning permit was referred to the Executive Director of Heritage Victoria as a determining referral authority, a permit is not required.Specific exemptions may also apply to your registered place or object. If applicable, these are listed below. Specific exemptions are tailored to the conservation and management needs of an individual registered place or object and set out works and activities that are exempt from the requirements of a permit. Specific exemptions prevail if they conflict with general exemptions. Find out more about heritage permit exemptions here.Specific Exemptions:General Conditions: 1. All exempted alterations are to be planned and carried out in a manner which prevents damage to the fabric of the registered place or object. General Conditions: 2. Should it become apparent during further inspection or the carrying out of works that original or previously hidden or inaccessible details of the place or object are revealed which relate to the significance of the place or object, then the exemption covering such works shall cease and the Executive Director shall be notified as soon as possible. Note: All archaeological places have the potential to contain significant sub-surface artefacts and other remains. In most cases it will be necessary to obtain approval from Heritage Victoria before the undertaking any works that have a significant sub-surface component. General Conditions: 3. If there is a conservation policy and plan approved by the Executive Director, all works shall be in accordance with it. Note: The existence of a Conservation Management Plan or a Heritage Action Plan endorsed by Heritage Victoria provides guidance for the management of the heritage values associated with the site. It may not be necessary to obtain a heritage permit for certain works specified in the management plan. General Conditions: 4. Nothing in this declaration prevents the Executive Director from amending or rescinding all or any of the permit exemptions. General Conditions: 5. Nothing in this declaration exempts owners or their agents from the responsibility to seek relevant planning or building permits from the responsible authorities where applicable.Minor Works : Note: Any Minor Works that in the opinion of the Executive Director will not adversely affect the heritage significance of the place may be exempt from the permit requirements of the Heritage Act. A person proposing to undertake minor works may submit a proposal to the Executive Director. If the Executive Director is satisfied that the proposed works will not adversely affect the heritage values of the site, the applicant may be exempted from the requirement to obtain a heritage permit. If an applicant is uncertain whether a heritage permit is required, it is recommended that the permits co-ordinator be contacted.

General:

* Interments, burials and erection of monuments (excepting above ground interment structures such as mausoleums which exceed the size and form of monumental graves), re-use of graves, burial of cremated remains, and exhumation of remains in accordance with the Cemeteries Act 1958 (as amended).* Stabilisation, restoration and repair of monuments.

* Emergency and safety works to secure the site and prevent damage and injury to property and the public.

* Monument works undertaken in accordance with Australian Standard AS4204 Headstones and Cemetery Monuments.

* Demolition, alteration or removal of buildings not specified in the extent of registration.

* Painting of previously painted structures in the same colours provided that preparation or painting does not remove evidence of the original paint or other decorative scheme.Shelters B4, B5, and B6:

* Minor repairs and maintenance which replace like with like.

* Repainting of previously painted surfaces in the same colours.Entrance gates and Alma Road gates

* Minor repairs and maintenance.Layout and landscape

* Repairs, conservation and maintenance to hard landscape elements, buildings and structures, ornaments, roads and paths, fences and gates, drainage and irrigation systems.* Maintenance of roads and paths and gutters to retain their existing layout.

* The process of gardening and maintenance to care for the cemetery landscape, planting themes, bulbs, shrubs, and trees and removal of dead plants.

* Management of plants in accordance with Australian Standard, Pruning of amenity trees AS 4373.

* Removal of vegetation to maintain fire safety and to protect monuments, paths, registered buildings and structures.

* Removal of plants listed as noxious weeds in the Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994.

* Replanting to retain the existing landscape character.

ST KILDA CEMETERY - Permit Exemption Policy

The cemetery is important for its nineteenth century and twentieth century elements including layout, ornate fence and gates, shelters, plantings, and monuments and memorials. The brick walls and ornamental fence and gates are considered to be of primary significance for their intactness, integrity and completeness as a structure enclosing the cemetery. While there are exceptional examples of stonemasonry and ironwork exhibited in a number of memorials, the over-riding importance of the cemetery rests in the historical value of the graves, which represent a rich cross-section of contributions made to the settlement and cultural life of Victoria. Of primary significance are: the earliest headstones and surrounds of the 1850s and 1860s and the cast iron grave memorials dating from the 1870s.

The purpose of the permit exemptions is to allow works that do not impact on the significance of the place to occur without the need for a permit. Alterations that impact on the significance of the place are subject to permit applications.

-

-

-

-

-

GLENFERN

Victorian Heritage Register H0136

Victorian Heritage Register H0136 -

BELMONT FLATS

Victorian Heritage Register H0805

Victorian Heritage Register H0805 -

ST GEORGES UNITING CHURCH

Victorian Heritage Register H0864

Victorian Heritage Register H0864

-

'NORWAY'

Boroondara City

Boroondara City -

1 Mitchell Street

Yarra City

Yarra City

-

-

Images See all images