MELBOURNE CRICKET GROUND

BRUNTON AVENUE EAST MELBOURNE, MELBOURNE CITY

-

Add to tour

You must log in to do that.

-

Share

-

Shortlist place

You must log in to do that.

- Download report

Statement of Significance

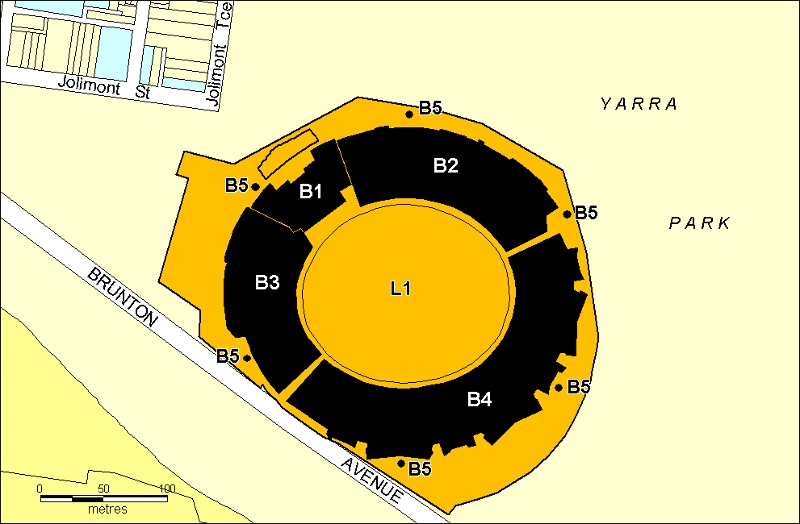

The Melbourne Cricket Ground was established in 1853 when 10 acres of land at Yarra Park in Jolimont was set aside for the use of the Melbourne Cricket Club, the purpose of the reserve being 'to promote the recreation and amusement of the people and ... to provide a site or place for the playing of cricket within the City of Melbourne in our said Colony.' Since 1862, the ground has been administered by a government-appointed trust (the MCG Trust) which continues to delegate its day-to-day management to the Melbourne Cricket Club. From its beginnings as a simple paddock-like ground with a modest pavilion and with limited grandstand and other facilities scattered around the perimeter, the Melbourne Cricket Ground has evolved and expanded through a process of phased redevelopment and renewal into a major piece of sporting infrastructure serving the metropolitan area and the State as a whole. Currently, the stadium comprises four principal stands, the MCC Members Pavilion (the third on the site, designed by Stephenson and Meldrum and completed in 1927), the Northern (Olympic) Stand (designed by AW Purnell and completed in 1956), the Western (Ponsford) Stand (designed by Tompkins, Shaw & Evans and completed in 1968) and the Great Southern Stand (designed by Daryl Jackson in association with Tompkins Shaw & Evans and completed in 1992), the oval, light towers (1984) and Australian Gallery of Sport (1986).

How is it significant?

The Melbourne Cricket Ground is of historical, social, aesthetic and architectural significance to the State of Victoria.

Why is it significant?

The MCG is of historical and social significance at a State, national and international level, as one of the oldest and largest capacity contained sporting venues in the world and one of the best-known of international cricket grounds, and as the pre-eminent venue for top-level cricket in Australia since the mid to late nineteenth century. Since the late nineteenth century it has also been the main venue and symbolic home of Australian Rules Football in Melbourne, making it of great historical and social significance in a State and metropolitan context, and - following the expansion of the Australian Football League to include interstate clubs - in a national context. The MCG is also historically and socially significant as the main venue and ceremonial focus for the 1956 Melbourne Olympic Games, and for its associations with numerous other sports and events.

The MCG is also of historical and social significance for its association with the Melbourne Cricket Club, the oldest club in Victoria and a major force in the development of cricket and other sports in Victoria from the nineteenth century. This association is reflected in the Members Pavilion, which is the third such pavilion constructed for the purpose. As well as being the repository of Victoria's cricketing traditions, the pavilion occupies the prime position for viewing events, particularly cricket, and allows members access to a range of private facilities such as the dining room and the long room.

In the broader context, the MCG is also of historical and social significance for its egalitarian image as the 'people's ground' and its long tradition of serving the people of Victoria. The MCG is socially significant as a living icon, a focus of attention in which importance lies in participating in events as well as experiencing the place itself.

The MCG is of aesthetic significance primarily for its overall form and scale. The MCG is a landmark on the edge of the city, a vast stadium which retains its traditional parkland setting. Whether full or empty, the stadium is of considerable aesthetic power and significance and is a place of energy and great atmosphere.

Within the broader conception of the MCG, there are elements with their own architectural significance. Firstly, the Members Pavilion by Stephenson and Meldrum (1927), is architecturally important as a large and relatively intact grandstand from the interwar period, although an appreciation of its impressive facade is marred by the somewhat intrusive Australian Gallery of Sport of 1986. Secondly, the Great Southern Stand by Daryl Jackson in association with Tompkins Shaw and Evans (1992) has been the recipient of a wide range of design awards and has generally been received with acclaim by architectural critics.

-

-

MELBOURNE CRICKET GROUND - History

Taken from:

MELBOURNE CRICKET GROUND, YARRA PARK, JOLIMONT, CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN

Allom Lovell & Associates in association with Bryce Raworth Conservation - Urban Design

The inaugural meeting of the Melbourne Cricket Club was held on 15 November 1838 and the first cricket match was held the following week, on a paddock near the corner of William and La Trobe Streets (now the site of the Royal Mint). Founding members of the MCC included Frederick Powlett, the surveyor, Robert Russell, Captain G B Smythe of the Mounted Police and the overlanders, Peter Snodgrass and William Ryrie. Shortly afterwards, the action moved to a new cricket ground, located west of Spencer Street, in the vicinity of the present-day Spencer Street railway station. No permanent buildings were erected, the players making do with a tent.

Some five years later, in 1848, the club moved to a site on the south bank of the Yarra River, the use of a ten acre paddock there having been granted by Superintendent La Trobe. On the strength of this the club put up a wooden booth, fenced the oval and turfed part of the area.

Unfortunately, however, the ground lay directly in the path of Australia’s first railway line, the Melbourne-Sandridge line, (developed by the Melbourne and Hobson’s Bay Railway Co in the early 1850s, and officially opened in September 1854), and the Club was forced to relocate its ground a third time. As compensation for the loss of its Southbank ground, Governor La Trobe offered the MCC two alternative sites in the Government Paddock at Richmond. The Committee of Management selected a plot some 250 yards in diameter which was just a short distance south-east of La Trobe’s own property, and which was described as being ‘in the hollow to the right of the footbridge leading across the paddock’. On 23 September 1853, the Club was granted permissive occupancy of 10 acres of land (to be used for cricket only) for a five year period. The Governor also granted permission to erect such buildings as were required, but did not provide for a right of carriageway.

The selection of this location for the new Melbourne Cricket Club’s metropolitan cricket ground was just one in a series of developments which established Yarra Park as a zone of passive and active recreation serving the city. Then, as now, Yarra Park extended south from Wellington Parade to the Yarra River and was bisected by the railway line running from the city to Richmond. During the late nineteenth century, the broader Yarra Park reserve accommodated a series of recreational facilities, including a total of four cricket grounds (the MCG, the Richmond Cricket Ground, and, south of the railway line, the Scotch College and Lonsdale cricket grounds (Figure 5). For a time, it also accommodated a zoological gardens reserve fronting onto the river. Yarra Park was also developed as one of the city’s parks, complementing the others in East Melbourne and the city. While the Yarra Park reserve has undergone many changes since this time, it is still essentially a large green area which provides a setting for a number of sporting facilities, a setting, which in the case of the MCG is relatively little changed since the late nineteenth century.

One of the first structures to be built at the Melbourne Cricket Ground in this early period was the original Members Pavilion. Constructed in 1854, this was a picturesque timber building located in the Members Reserve on the north-north-western side of the ground. The building was designed with a verandah enclosing very limited tiered seating and looking out over the Members Reserve to the ground itself. Its principal elevation originally featured a gable with decorated gothic bargeboards at either end; in 1861, a central round-headed clock gable was added, and the building was enlarged through the addition of a new rear wing (Figure 8).

Some of the earliest illustrations of the ground date from the late 1850s and early 1860s and show the Members Pavilion as the main permanent building, but with sundry other structures scattered around the perimeter of the oval, including a series of tents and marquees and a band pavilion. The ground appears to have been gradually fenced over these early years, but overall it still had a relatively informal appearance (Figure 9).

Development proceeded more rapidly in the 1860s. In 1861, Robertson & Hale called tenders for the erection of a grandstand at the MCG for Messrs Speirs and Pond, proprietors of the Cafe de Paris in Bourke Street. Just two years later, in October 1863, work began on a grandstand on the south-western side of the ground, constructed in honour of the first visit to the colony by an English touring team, Mr Stephenson’s XI. The tour was sponsored not by the Club directly, but by the publicans Speirs and Pond. Larger than any cricket pavilion in the world at the time, the grandstand was said to be some 700 feet long, and could accommodate 6,000 (Figure 10). All of its lower tier was given over to publicans stands; it was claimed that collectively they would have some 500 cases of beer on hand for the big game.

At the end of the 1860s, the ground itself was redesigned by R C Bagot, who had been responsible for the design of Flemington Racecourse. Working with the Government Botanist and Director of the Botanic Gardens, Ferdinand von Mueller, Bagot altered the shape of the ground to make it a perfect oval, introduced drainage pipes underneath the ground and replanted and returfed the ground.

Substantial development and redevelopment occurred at the Melbourne Cricket Ground from the mid 1870s up until the turn of the century. This development took the form of a series of new stands and a new Members Pavilion and was generally concentrated on the northern side of the ground, in the Members Reserve and to some extent to either side. By contrast, a large proportion of the public area or ‘outer’ remained relatively undeveloped at the turn of the century.

In 1873, following the success of the Speirs and Pond stand, a new grandstand was built, this one constructed by Messrs Halstead, Kerr and Co. Like the earlier grandstand, the new stand also accommodated a range of refreshments at its lowest level, including a great public dining room, bars, oyster stalls and a fruit stall. Those who had the need could even send electric telegraphs from a specially designed telegraph room. Patrons of the outer also benefited from improvements to the amenity of the ground; new seating was constructed around the ground and a new sloping embankment built up in the outer, ‘where patrons, even though sitting, could gain an uninterrupted view over those in front.’ An old cow shed in the outer was turned into a skittle alley and was a great success, and ten ticket boxes were constructed around the ground, reducing the crush. The level of comfort and amenity experienced by visitors to the Ladies’ Reserve was also said to have improved in this period; MCC historian, Keith Dunstan quotes the Club’s claim of the day, that the Ladies’ Reserve ‘is now a place where the fair visitors can see and be seen to advantage, and when tired of watching the sterner game, can turn to the quieter attractions of croquet and flirtations’.

Several major new buildings and numerous less substantial structures were constructed in the next decade. In 1877, the Club constructed the famous double-sided grandstand on the north- eastern side of the ground. This was followed in 1881 by a new members pavilion, and, following the destruction by fire of the double-sided stand in 1885-6, by another major new grandstand. Other works undertaken in the late 1870s and early 1880s included the construction of an additional row of timber seating around the ground, the construction of a new standing gallery, various fencing works, construction of various ‘permanent’ refreshment booths, a ladies’ pavilion, and players’ dressing rooms, and the introduction of gas services to the main grandstand. Most of these works were supervised by architects Conlon and Salway. In the mid-1890s, bowling greens were also established at the ground following the formation of the MCC Bowls Section in 1894. The greens were constructed on an acre of land immediately west/north-west of the ground acquired in a land swap (for the site of the former Richmond bowling club to the east) involving the Lands Department and the Melbourne City Council.

Other improvements made in the 1880s included the addition of sightboards located at strategic positions around the ground, and an early version of the modern press-box, a two-storey timber building which accommodated the scorers, press and telegraph operators. The building featured a series of modern innovations; of particular note were the special speaking tubes which connected the press to the scorers and telegraph operators below.

An 1897 MMBW drainage plan of the site shows the layout of the ground at the end of the nineteenth century. The two major buildings, the Members Pavilion and the main grandstand of 1885-6 (see below), were located on the northern side of the site. The eastern and southern sides of the ground comprised the outer, with a series of refreshment buildings and the like dotted around the perimeter of the ground but with no major grandstand structures. To the south of the Members Pavilion and included in the Reserve, was an open-sided stand, known as the Smokers’ Pavilion. The bowling greens and tennis courts were also located in this area.

The remainder of the ground, covering approximately the area now covered by the Great Southern Stand, was taken up by open seating and standing room on a raised embankment. Various refreshment booths, bars and other facilities for spectators were located around the perimeter of the oval, with the main scoreboard located on the eastern side of the ground.

The ‘Double-Sided’ Grandstand, 1877-1885 (demolished)

Constructed at a cost of £4,678, the design of the double-sided grandstand was the result of a competition, the winning architect being George Browne. Keith Dunstan explains the basis of the design (see Figure 11.)

This was a stand in the true English tradition. It faced both ways and it held two thousand people. At the end of the cricket season it would be reconstructed so that the seats faced the other way. This meant that during the summer the spectators could watch the cricket in the M.C.G., then in the winter the football out in Richmond Park. In 1876 the club did not tolerate football on the sacred turf of the M.C.G. Few seriously believed that then that a ground could be a sea of football mud in August and a cricket playing wicket in September.

A contemporary description noted that the building was:

in reality, a two-storey building, the ground floor being occupied by ladies’ rooms, a skittle alley, a large luncheon room, and two refreshment bars. The sitting accommodation was above this, and was reached from the lawn in front by three broad stairways.

At the end of each season, contractors were employed to ‘turn the stand’, (ie: reverse the seating); in 1878 this task was said to have been undertaken in the record time of thirteen and a half hours.

The double-sided stand was the main accommodation at the ground for the next few years (the earlier stands appear possibly to have been demolished) , and was referred to as ‘the Stand’ in Annual Reports of the day. It was destroyed by fire in 1885. Just after the fire, the Argus commented that ‘from a purely architectural point of view it was not a very elegant structure, but its plainness was more than counterbalanced by its usefulness.’

The Second Members Pavilion, 1881-1926 (demolished)

By the early 1880s, the Members pavilion was considered inadequate for the Club’s purposes and plans were made for the construction of a new building. The new building, it was considered, would improve the status of the MCC and its ground and would provide the basis on which the membership numbers could be increased.

If carried out [the planned new building] will serve to greatly increase the prestige of the Melbourne Cricket Club, already the foremost in Australia. It has been obvious for some time that the present building is wholly inadequate for the requirements of the members, but of course there is some little difficulty in obtaining the necessary funds. Arrangements are in contemplation by which this difficulty will probably be overcome, and the club will then possess the most complete and beautiful cricket ground perhaps in all Australia . . .

Accordingly, in 1881 a new Members pavilion was designed for the Club by prominent Melbourne architect, William Salway (Figure 16). The original timber pavilion was advertised for sale (‘suitable for cricket clubs or cottages’) and was removed from the site. It was replaced by a much larger pavilion which could accommodate many more of the Club’s members and in far greater comfort:

[O]n the ground floor there was a refreshment room large enough to accommodate 150 in comfort. There was a secretary’s office. There was a refreshment bar complete with liquor and oyster counters. There was a billiard room brilliantly lit, with two tables, whilst on the second floor there were reading rooms and visitors’ dressing rooms. There was also a veranda and a balcony which could accommodate 350 people, and, seeing that the roof was flat and galleried, here was standing room for another two hundred, and this position commanded a magnificent view of the suburbs and surrounding country. Speaking tubes were connected throughout. The exterior of the building was composed of dark brick and the woodwork was beautifully varnished. It was considered the finest cricket pavilion in the world.

Though considered very commodious when completed, the new pavilion was extended just a few years later, in 1887. The building appears to have undergone further remodelling works under the supervision of architect William Pitt in c. 1906. The first detailed plans of the second Members Pavilion date from this period and show the layout of the pavilion and the uses of the spaces within the building at that time (Figure 18). The ground floor of the pavilion contained players dressing rooms, offices for the secretary, porter and caretaker, a kitchen and a cricket store. The main entrance to the pavilion was also on this level. The entrance led into a generous foyer / crush space and then either to the stairs or to the central meeting room and main members bar, which featured a large island bar. A series of windows looked over to the verandah which accommodated a limited amount of seating. Above, at first floor level, there were more players’ dressing rooms, opening onto separate players’ balconies, either side of the main members balcony. This level also featured a large luncheon room, billiard room and meeting room, like the one below looking over the main balcony. Separate facilities for the MCC Committee were located on this level, including a luncheon room, committee room and committee balcony.

The second Members Pavilion was demolished in the late 1920s, to make way for the third, and current, Members Pavilion.

The Northern ‘Public’ Grandstand, 1885-1954 (demolished)

In August 1884, just a few years after the completion of the new Members Pavilion, the club suffered a major setback, when the main ‘double-sided’ stand of 1877 was destroyed by fire. Spectators had to be accommodated in temporary and relatively makeshift accommodation for many months. Still owing money on the construction of the ‘double-sided’ stand, the MCC embarked on another major building programme, this time for a large new grandstand designed by architect William Salway. The new stand was built on the northern side of the ground and was completed by late 1885 at a cost £11,490. Straddling the boundary between the members reserve and the area of the ground which accommodated the general public, the stand contained general seating as well as an area of seating and dining facilities set aside for the exclusive use of MCC members and their families (Figure 17). This stand was greatly expanded in 1896-7 with the addition of a ‘double-deck’ pavilion at either end (Figure 19). These pavilions are thought to have been designed by architect William Pitt. The 1897 grandstand extensions provided an additional 1,100 seats for the general public and 900 for members. New facilities in the enlarged members area of the stand also included new tearooms and a gymnasium. The Salway/Pitt grandstand was demolished in the early 1950s to make way for the new Northern (Olympic) Stand.

In the first decade of the twentieth century, prominent Melbourne architect William Pitt appears to have been engaged by the Club to examine the issue of accommodation for spectators at the ground, both members and non-members. A collection of drawings by Pitt and his partner, Albion Walkley, held by the State Library of Victoria, shows a series of proposals dating from this period for new stands and other structures at the ground.

Though the documentation is not clear, in the end it appears that at least three new stands were constructed before World War I, all designed by William Pitt. The more architecturally pretentious of these was the Grey Smith Stand (1906), located south-west of the Members Stand and within the Members Reserve. By comparison, the other two Pitt-designed stands, the Wardill and Harrison Stands (1908-12) were both located in the public area and were of a simpler grandstand design with limited amenities.

The Grey Smith Stand, 1906-c.1966 (demolished)

The Grey Smith Stand replaced the Smokers Pavilion and old tennis courts in the Members Reserve and was named for Frank Grey Smith, a member of the MCC from 1849 until his death in 1900. Its foundation stone was laid by the then Premier, Sir Thomas Bent, in 1906.

As well as providing additional seating for MCC members, the Grey-Smith Stand offered a range of new facilities for both members and players. The stand was designed to complement and augment the facilities already provided in the main members pavilion, which appears to have been remodelled by Pitt at around this time. The capacity of the Grey Smith Stand is thought to have been in the order of 2,000. At ground floor level the stand contained two players’ dressing rooms, a ladies’ tearoom and members bar, while above were two levels of seating. It would appear that the players’ dressing room facilities were shared between the 1881 Members’ Pavilion and the Grey Smith Stand in this period; indeed, the plans show that the dressing rooms in Grey Smith were more substantial than the rooms in the existing Pavilion.

Designed in a typical, albeit relatively elaborate, Edwardian manner, the Grey Smith Stand was constructed of red brick relieved by bands of render. The roof appears to have been of slate and featured three sheet metal fleches and three flagpoles. The rear elevation was dominated by a series of Romanesque brick arches on the upper level enclosing both paired multi-paned round-headed windows and circular multi-paned highlight windows. The interiors of the stand featured the extensive use of pressed metalwork.

Part of the ground floor of the Grey Smith stand was later adapted for use by the MCC bowling club and a porch for the bowling club added to the rear (west) of the stand.

The Grey Smith Stand was demolished in 1966 to make way for the new Western (Ponsford) Stand.

New Stands in the Outer – The Wardill and Harrison Stands, c.1910-1930s (demolished)

A great improvement was made to conditions in the outer in 1912 when a large new covered stand, the Wardill Stand, designed by William Pitt and named after the Club’s long-time secretary, Major Ben Wardill, was constructed on the southern side of the ground. A relatively simple structure with only a single tier of seating, the Wardill Stand had a capacity of 3,000. It was demolished in 1936 to make way for the new Southern Stand.

Another stand was also constructed around this time in the outer; this is assumed to have been an open stand and possibly to have been the basic structure of the Harrison Stand. The Harrison Stand was also located in the outer, some distance east of the Wardill Stand. It was a simple roofed stand with little or no discernible architectural detailing. Council records note an application for the construction of a roof over an existing stand in June 1923; this may have been for the completion of the Harrison Stand. Like the Wardill Stand and all other structures on the southern side of the ground, the Harrison Stand was demolished in the 1930s to make way for the Southern Stand.

A new scoreboard, referred to as No. 1 Scoreboard was also constructed on this side of the ground in the early twentieth century.

From the end of WWI, the size of crowds attending the ground, particularly those attending football finals, had raised concerns about the safety and comfort of the public and as early as 1919 the Trustees had approached the Minister of Lands seeking an extension of the MCG reserve. As a result of increasing pressure to provide better facilities for increasingly large crowds, the mid- to late-1920s saw the redevelopment of parts of the western and north-western sides of the ground, with the construction of the Concrete Stand (1926) and the new Members Pavilion (1927).

Despite the construction of the new stands in the mid-1920s, the question of inadequate accommodation for the average member of the general public was one which continued to be hotly debated towards the end of the decade and well into the 1930s. In October 1930, just after his appointment as a new trustee of the Melbourne Cricket Ground, the Member for Lands, Mr Bailey, made his views on the subject known in comments made to the press:

the Minister of Lands stated that as the workers comprised the great bulk of the spectators at football and cricket matches, and therefore provided the greater part of the gate money, he considered that it was time they had representation on such bodies as the trustees of the Melbourne cricket ground. Palatial and exclusive grandstand accommodation was provided for members of the cricket club. Others who could pay the high charges for membership of clubs could go into the grandstand enclosure, but there was very limited seating accommodation for the people who went into the part known as the outer reserve, while a vast number could not find seats, and had to stand in the heat or rain, and watch the game as best they could, under unpleasant conditions. While recognising that it would be impossible to provide seating and sheltered accommodation for the vast crowds at the most important matches, much remained to be done in the way of providing more conveniences for the people who could not afford to pay the higher admission charges to the more exclusive enclosures, but who nevertheless contributed substantially to the maintenance of the various sports and the facilities in other parts of the ground.

The debate heated up dramatically in January 1933, when a record crowd of just under 70,000 turned up to see Donald Bradman make 103 against England in the Second Test in the infamous ‘bodyline’ series. Thousands were turned away and more left the ground because of the difficulties of simply getting into the ground. One man fell from a stand, severely injuring his back and, as the press reported, there were many unpleasant scenes, including sweets stalls and bars operating immediately adjacent to men’s conveniences, scenes which the Herald noted would ‘not be tolerated at a country race meeting’. The Age took up the cudgels on behalf of the common man and woman:

There is an utter disregard for the convenience of the patrons of the outer reserves. They are forced as an alternative to the glaring sun to eat food under the stands, amidst clouds of dust and in close proximity to primitive sanitary conveniences. The whole of the arrangements call out for complete reorganisation. Admittedly complete reform involves large commitments, but the sanitation matter cannot wait for large schemes.

All the dailies commented on the method by which the ground was managed and the unequal standard of the facilities enjoyed by cricket club members as opposed to those available to football fans. One paper blamed the trustees:

Much more accommodation is required at the Melbourne Ground for other occasions than those of Test matches. This great public asset should serve for many great sporting gatherings and be managed according to a far bigger public policy. The conditions yesterday in some of the public parts of the ground were offensive to public decency . . . Unless the trustees show immediately a sense of their responsibility, and take action towards making the ground what it ought to be, and unless conditions are created by which the members can be greatly increased, it will be the obvious duty of the trust.

The Herald, on the other hand, commented that the problem was partly related to the management structure but was also a financial one. The trustees delegated certain powers and responsibilities in terms of the management of the ground, including the provision of accommodation at the ground, to the Melbourne Cricket Club, which, the Herald pointed out, was in an unenviable position:

… the MCC … only has its members subscriptions and 10 per cent of gate money, less trustees expenses, to depend upon for the whole care and maintenance of the ground… The greater part of the vast revenues received at the gates is diverted through such bodies as the Victorian Cricket Association and the Victorian Football League, and does not contribute to the improvement of the ground.

As the MCG has no security of tenure … and has no claim even on the buildings which it has erected at its own expense, it is scarcely in a position to raise the money, even if it is prepared to do so.

The end result of all the public debate in the 1920s and 1930s was that three substantial new stands were built in this period. These were the Concrete, Open or Scoreboard Stand (1923-6), the new Members Pavilion (1927), and the Southern Stand (1936-37).

The Concrete Stand, 1923-66 (demolished)

In 1926, land previously taken up by the old tennis courts, yard and scoreboard to the south of the Grey Smith Stand was developed for a new open-topped public stand which was referred to as the Concrete Stand. The construction of this stand was prompted by the large crowds attending the football finals and with a standing room capacity (the stand did not provide any seating) of 10,000 increased the number of people which could be accommodated in the outer. The rather distinctive form of the Concrete Stand, which appears possibly to have been designed by architects Ballantyne and Hare, is visible in numerous photographs of the ground dating from 1920s and 1930s. The stand accommodated the main scoreboard and was sometimes known as the Scoreboard Stand. It also had two small bars and toilet accommodation for both men and women and some limited storage facilities.

In the 1930s it was anticipated that the Concrete Stand would be incorporated into the new Southern Stand of 1936-7, but this did not eventuate and the two co-existed for some 30 years. The stand was eventually demolished in 1966 to make way for the new Western, or Ponsford Stand.

New Members Pavilion, 1927-8

Soon after the completion of the Concrete stand, work also began on the present Members Pavilion. Designed by architects Stephenson and Meldrum and constructed in 1927-28, the new pavilion replaced the earlier structure on this site, joining the 1906 Grey Smith stand within the members enclosure. This building is now the oldest surviving major building at the ground.

According to the Club’s historian, Keith Dunstan, news that the old pavilion was to be demolished was received with regret and some unhappiness by many, particularly the older members. There were spaces within the building which were imbued with tradition and particular meanings. Dunstan mentions in particular the room on the right-hand side of the door, home for many years to the first eleven of the club and for other representative sides, including the Australian XI. Some were saddened by the loss of their special seats; as Dunstan notes, though no member had an officially reserved seat,

always the same people could be found in the same places. Perhaps it was one of the fifty seats under the press balcony, others could be found up on the balcony itself, and then there were the roof regulars. J McCarthy Blackham, the prince of wicketkeepers, always held court up there with a group of his friends. The veteran players all had their picked and loved positions. Now they would have to move elsewhere.

[It is interesting to note that a version of this tradition, in the form of unofficial reserved seating, is still carried out in some areas of the current Members’ Pavilion].

Despite these regrets, the Argus pointed out that change was well overdue and that there were very good reasons for the construction of a new pavilion, foremost among them the greatly increased membership of the club:

There are now nearly 6000 MCC members and there are 4150 names on the waiting list, and some of them have been there for the past six years. For many years, owing to the lack of accommodation, members have wondered whether it really was a privilege to belong to the club, for they found themselves crowded out of their own pavilion by representatives of other bodies. In the new pavilion I understand a notice which has long been disregarded, ‘Members Only’, will be strictly observed. It will make membership of the club what it used to be, a privilege and a pleasure. Now there are so many complimentary tickets that the character of the members reserve has changed. The pity is that the old building could not have been retained and the new pavilion erected on another site.

The size of the new members pavilion far exceeded that of the earlier pavilion and additional land was required for its construction. A complex deal was conceived involving a reduction in the area of land occupied by the bowling club and the construction of new bowling greens in a position slightly further south-west. New entrances to the Members Reserve were introduced at this time.

When compared with the 1881 Salway pavilion, the new pavilion offered greatly expanded accommodation and increased comfort for members, as the Club reported to its members in the 1927-8 Annual Report:

The accommodation in this building is spacious, consisting of a Lower Balcony to seat 800 persons; an upper Balcony with seating for about 2,000; a glass fronted Members Lounge will be an important feature; a Dining-room to seat 200 persons; Buffet for quick, light lunches; large Bar (on ground floor); Drying-room; Hot and Cold Showers in Locker-rooms; complete and up-to-date Kitchen equipment, to provide hot and cold meals; complete sanitary arrangements and excellent lighting. Including the large clock to be erected in the front of the Upper Balcony, all subsidiary clocks throughout the building will be electronically controlled, thereby ensuring uniform time. Furnishings will be in keeping with the construction of the building. Time has not been spared in the careful consideration of details and Members requirements, and your Committee feel that members will be proud of the new edifice, which should be one of the finest in the world.

Identified in the Annual Report as ‘an important feature,’ the ‘glass-fronted Members Lounge’ was to become the best-known of all the spaces within the Members Pavilion. Over time, this space became known as the Long Room, a reference to the Long Room in the Marlyebone Cricket Club’s pavilion at Lord’s in London. According to MCC historian, Keith Dunstan, the exact origins of the association with the Long Room at Lord’s are unclear but the association itself is not in doubt. Melbourne’s Long Room is not in any sense a copy of the Lord’s version, but both are characterised by a traditional character and presentation. It is interesting to note that while the earlier (1881) pavilion included bar and luncheon room facilities, and a meeting room overlooking the first floor balcony, the use of the term ‘Long Room’ is thought to have been coined only following the construction of the new pavilion in the 1920s.

Development of the Southern Side of the Ground, 1936-37

As noted above, the MCG Trustees came under intense pressure in the early 1930s to improve the accommodation and level of amenity in the outer and to overhaul all the sanitary arrangements across the ground. While improvements in toilet accommodation were made as a matter of urgency, a more fundamental approach clearly was warranted and in October 1933 the trustees received a report from architects Oakley and Parkes on the general issue of accommodation at the ground. The architects had been asked to consider the best method by which the accommodation in the outer could be increased to 75,000. Their recommendation was that all existing buildings on the southern side of the ground – with the only exception the 1926 Concrete Stand – be demolished and a new stand be constructed, altering and extending the Concrete Stand and incorporating it into the new stand. The new stand, they claimed, would have a combined seated and standing capacity of 75,186. On occasions when this full capacity was not required the stand could accommodate 36,266, all seated.

The Southern Stand, 1936-1992 (demolished)

The new Southern Stand was designed not by Oakley and Parkes, but by another practice, Arthur W Purnell & Pearce. The construction of the proposed new Southern Stand cost around £100,000 and commenced in early 1936. Though it did not, in the end, incorporate the Concrete Stand, the new Southern stand was bigger than any other at the ground and included - in addition to extensive seated and standing accommodation - changing rooms for footballers and cricketers, refreshment booths, and casualty rooms. It was almost, but not quite, finished for the Third Test against England in the summer of 1936. However, the ground was so crowded on the first day, with an attendance of 78,630, that some were not prepared to wait and climbed over the barriers onto the uncompleted stand.

The Southern Stand was demolished in the early 1990s to make way for its namesake, the Great Southern Stand.

Camp Murphy: The MCG During Wartime

As in WWI, the outbreak of war in 1939 meant that the international cricket programme was suspended and as it became obvious that the conflict would be a long and difficult one, the Sheffield Shield cricket and district cricket pennants were also suspended for the duration. It was inevitable that such a large facility located so close to the city would be put to use as part of the war effort and in early 1942 the Commonwealth decided to use the MCG as a staging camp for military forces. The MCC was left only with the bowling pavilion and its greens and the Melbourne Football Club played its home matches at the Richmond Cricket Club’s ground. The US Air Force occupied the ground for some months, followed by the Marines. It was a hive of activity; numbers of US servicemen accommodated at the ground reaching a peak during WWII of 14,000. Naturally, the Members Pavilion was the centre of activity for the more senior personnel; officers were given the use of the Long Room, with sergeants accommodated on the level above. The other stands were put to use for a range of facilities, ranging from kitchens to the armoury, and hundreds of tents were pitched on the oval. The US Army moved out in 1943 and the Royal Australian Air Force moved in, becoming No. 1 Personnel Depot. From this time until the end of the war, all airmen moving north or overseas or returning home passed through the MCG.

The Development of a Masterplan

After a nine month period during which the fibro-cement sheeting that boarded up the stands was removed and the seats were put back, the MCG reverted to its proper use as the city’s pre-eminent sporting venue. The first event was a club football match, Melbourne vs Hawthorn, held on 17 August 1946, and it was with much fanfare and excitement that the first Test match at the MCG in ten years was held in January 1947.

At the end of the 1940s, however, plans for an even bigger event were put on the table, when the MCG became one of several venues to be touted as the main stadium for the first Olympic Games to be hosted in Australia. In the lead up to the Games it had been considered the obvious choice, regarded by the Olympic Organising Committee as the finest arena in the southern hemisphere. When it came to examining the ground in detail, however, it became clear that major changes would be required before the ground was ruled suitable as an Olympic venue. Many thought it was a bad choice; it was not completely flat as required, it might be out of use for a year, some even said it was too big and that spectators would be too far from the action.

The Trustees too were reluctant; the degree of physical intervention was so great and the extent to which the normal pattern of use of the ground would be disrupted was considered unacceptable. With the MCG knocked out, the other main contenders were the St Kilda Cricket Ground, Olympic Park and the Carlton Cricket Ground in Princes Park. Of these, the front runner was Carlton, and the decision to use Princes Park was approved by Olympic officials at the Helsinki games in 1952. By January 1953, however, it became apparent that the incoming Cain Labor Government had other ideas. The Premier, John Cain called in the MCC President, Dr McClelland, and asked him to reconsider holding the games at the MCG, as the Government had neither the desire not the money to finance another ground. In response, the MCC Committee formally resolved to offer the Government its wholehearted support for the relocation of the Games to the MCG. The matter was far from settled, however, and controversy continued to rage. Following a conference with all the interested parties – and there were many – the Premier decided the issue himself:

There is not room in Melbourne for two stadiums each with a capacity of 100,000 persons. They would be used for only about 12 days a year except when Test cricket was being played every four years. The income of the MCC from the four football finals is £4700. It is proposed to spend £850,000 on a new stadium. From where will we obtain the interest on that money? Our successors will have to shoulder the burden forever.

Cain made his decision clear with this final comment:

The Games can be held at Carlton so long as it is distinctly understood that the State Government does not make a contribution. The State Government will contribute for the Games to be held at the MCG.

Running parallel to the debate over whether to stage the Olympics at the MCG or another venue, was an ongoing investigation by the Trustees of redevelopment options for the ground. For several years leading up to the decision to stage the Olympics at the ground, the Trustees again had been under pressure to make improvements to accommodation at the ground. Increased population and the widespread introduction of the five day working week were blamed for severe overcrowding at the ground in the post-WWII period. Additional crowd control measures were introduced in these years, including mounted police stationed at the gates to control disgruntled patrons refused entry to the ground. Football finals and Test matches during 1949 were plagued by overcrowding problems and in September the following year there were chaotic scenes at the 1950 VFL Grand Final, the Age reporting that padlocks on several large exit gates were sawn through by patrons, allowing thousands to enter without paying. On the same day, first aid attendants reportedly treated more than 200 cases inside the ground, major brawls broke out across the ground and hundreds spilled onto the arena itself.

While the Trustees had been advised by at least one of its consultants to delay any major projects until such time as the building industry had recovered from the high costs and materials shortages typical of the post-war period, the problem was one which had to be addressed. By late 1948, the option favoured by the Trustees’ honorary engineers, Clive Steele and D J McClelland, was that the northern side of the ground should be redeveloped with a new stand and that the size of the ground be increased. By March 1949, this scheme had been enlarged to contemplate the full redevelopment of all stands other than the relatively new Southern Stand of 1937. (Figure 40) It was a scheme which, if fully implemented, would have increased the capacity of the ground to a massive 150,000. This ‘masterplan’ was adopted by the Trustees and in 1949 an application was made to the State Government for an additional four acres of land to accommodate the redevelopment.

When the decision was taken in 1952 to stage the Olympics at the MCG, plans for the first stage of the planned masterplan redevelopment of the ground were quickly prepared. Architect Arthur Purnell was engaged to prepare documentation for a new northern or Olympic Stand, much larger than the existing Public Grandstand, and taking up an additional two acres of land on the north side of the ground.

The developments of the early 1950s marked an important phase in the history of the ground in that the 1951 masterplan saw the adoption of the stadium concept for the MCG, an idea which had been to a degree implicit in the planning and form of the 1936-7 Southern Stand. Significantly, the adoption of the masterplan also reflected a desire by Government and the MCC to effect in the long term a major increase in the public capacity of the MCG to around 150,000. While this was never achieved, since this time the expectation has consistently been that the capacity of the ground should be maintained at around 90,000-100,000.

The Northern (Olympic) Stand (1956)

The new Northern Stand was a solid concrete structure with an amphitheatre of seats rising from the arena fence and with a capacity of 41,000 compared with 10,000 for the existing stand. As noted above, the stand was originally conceived as the first stage of a total redevelopment of the northern and western parts of the ground, a redevelopment which was also to include demolition and replacement of the present Members Pavilion. Facilities were to be upgraded to meet the standards established by the 1936-37 Southern Stand by Purnell & Pearce, and the new stand was to be by the same firm, by this time known as AW Purnell & Associates (project architect John Holgar) in association with engineer DJ McClelland. As was the case with the old public grandstand, the western end of the new Northern Stand was designed to incorporate facilities for the use of members of the MCC.

The old grandstand was demolished immediately after the visit to Melbourne of Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip in early 1954 and the construction of the new Northern Stand commenced in June the same year. The construction project, undertaken by contractor, E A Watt, suffered numerous delays caused by a series of rolling strikes, black bans and go-slows by the building unions. After the 1955 Grand Final, the bulldozers and graders moved onto the ground and pulled up the turf. In the process, the ground was completely regraded and 3000 cubic feet of ash drainage and over 5,000 feet of drainage pipes were installed. Amongst all the destruction, one eye was kept firmly on the future, and more than 3,000 tons of Merri Creek soil was put in storage for reinstatement following the Games. Despite enduring fears that neither the ground nor the stand would be ready for the Olympics, both were completed two months prior to the Olympics and in time for the 1956 Grand Final. The running track was laid immediately afterward. The Games were opened on 22 November 1956 and all went according to plan. The ground, by all accounts was an impressive sight, with its central area of vibrant green contrasting with the broad red ribbon of the running track.

The Construction of the WH Ponsford Stand

In 1966 the MCG Trustees began moves to implement the second stage of the masterplan of 1951, with a proposal to demolish the Grey Smith Stand in the Members Reserve, the Open Concrete Stand (known also as the Open Grille or Score Board Stand) and the old scoreboard itself in the Outer Ground and to construct a new stand in their place. The MCG Newsletter of November 1966 announced that the new Western Stand and extensions to the Southern Stand would accommodate more than 31,000 spectators (9,000 seats for members, 9,000 seats for members of the public and a total of 14,000 public standing accommodation). It also contained new air conditioned players changerooms, which featured a parquet floor, in Dunstan’s words, ‘just like the best banks’.

The decision to press ahead with the planned expansion of facilities at the MCG was regarded by many as a courageous one as the VFL had just begun construction of Waverley Park, the first large-scale stadium devoted entirely to Australian Rules Football. Nevertheless, architects Tompkins Shaw & Evans, working with engineers Milton Johnson & Associates, were engaged to prepare plans for the new stand, to be known as the Western or WH Ponsford Stand. The foundation stone for the stand was laid by Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh. The southern half of the stand is thought to have been completed for occupation in time for the finals series in 1967, with the completed stand officially opened on 10 August 1968.

The Australian Gallery of Sport and Olympic Museum (1984/6)

The Australian Gallery of Sport was constructed on the north-west side of the ground, directly adjacent to the Members Pavilion, in 1984-6. As noted above, the building was designed by MCC architects, Tompkins, Shaw & Evans. In 1989, the gallery changed its name to the Australian Gallery of Sport and Olympic Museum. The Olympic Museum was incorporated into the name as one of the few International Olympic Committee facilities in the world. Today, the building is one of the ground’s visitor major attractions. Commemorative Olympic marble panels were relocated from the Northern (Olympic) stand and fixed to the east wall of the building.

Light Towers (1984)

Reflecting the increasing popularity of night cricket and football, in 1984 six light towers were constructed around the perimeter of the ground, at an cost in the vicinity of $2,000,000. The towers were designed by engineers, Gutteridge Haskins & Davey. The proposal to construct the light towers caused a degree of controversy and some public opposition. More significantly, however, the project was also plagued by industrial warfare, the Builders Labourers Federation taking extended action over a union demarcation dispute, delaying the project and incurring significant extra costs. The towers were first used in February 1985.

The Great Southern Stand (1992)

In the mid-1980s - acting on the advice of a series of more business-oriented commissioners and its new Chief Executive Officer, Ross Oakley - the Victorian Football League undertook an analysis of all its operations. A strategy for the future of the League was developed which included transforming the competition into a national competition, thereby reducing the number of Victorian teams and the number of playing grounds. At the same time concerns began to be raised amongst the VFL Commissioners that both of football’s main venues, Waverley Park and the MCG, were below par and that there was not enough revenue in football or cricket put together to fix both. According to MCC historian, Keith Dunstan, the VFL undertook extensive research to see which of the mega-grounds was favoured, VFL Commissioner Peter Scanlon recalling, ‘It was interesting … Waverley did quite well and was the second most popular ground in Victoria by a long way, but the MCG was still ahead.’ At around the same time, Dunstan notes, the Melbourne Cricket Club was itself undergoing a process of internal review and looking to its future. In the course of this, the importance of football to the long-term future of the Melbourne Cricket Ground emerged as a major issue. Historically, the relationship between the MCC and the VFL had been at times an uncomfortable, even adversarial one. Many of these differences were set aside, however, and in 1987 and 1988 major discussions were held between the two which anticipated the VFL adopting the MCG as the ‘home’ of football in Melbourne for the long term. A significant breakthrough in hitherto informal discussions occurred in June 1988, when a letter from VFL CEO, Ross Oakley was sent to the then President of the MCC, Donald Cordner. In essence, Oakley’s letter proposed that the VFL and MCC enter into a long-term arrangement which would see the MCG become the ‘home’ of football. It anticipated that this would involve some ‘bold steps’ at the ground, including the rebuilding of grandstands, and acceptance of another ‘members’ area (for VFL members) at the stadium.

In December 1988 a deal was signed between the parties under the terms of which the VFL would agree to play at least one finals match each weekend at the MCG for the next 40 years, effectively meaning that all preliminary finals and grand finals would be at the ground. A new stand would be built in place of the old Southern Stand, which was suffering from concrete cancer. The new stand would have 73 corporate boxes, seven restaurants for the public and accommodation for 4,000 more people than the old stand. Significantly, a new members’ reserve – this time for football interests - was created as part of the new stand. A total of 12 sections of the stand would be reserved for the VFL and its members during home and away matches and 14 during the football finals. During the cricket season, there would be five sections reserved for the VFL. The stand would also contain offices for the VFL, which would relocate its offices from VFL House to the MCG.

Two prominent Melbourne architectural practices, Tompkins Shaw & Evans, long-time architects to the club, and Daryl Jackson, were jointly commissioned to design the stand. A team of six - Daryl Jackson, Brian Smith from Tompkins Shaw & Evans, two representatives of the MCC, Dr John Lill and John Mitchell, the Club’s project manager, Don Wilkinson, and Russell Bode, of Spotless Catering – embarked on a tour of the world’s newest and best stadia. Of particular interest to the team were issues such as ramp design and sightlines, as well as the latest in corporate box design. As the design for the new stand progressed, the issues of the cost of the stand and its financing were also addressed.

The projected cost of the new Southern Stand was huge, estimated at somewhere between $145 and $200 million. Apart from the Olympic Stand, towards which £100,000 was advanced by the State Government as an Olympic Games commitment, all of the previous stands grandstands at the MCG had been financed entirely by Melbourne Cricket Club members' subscriptions. Still the Club had no equity in the ground or its building and could not use its interest in the ground as collateral. Special financial arrangements were made based on a long-term contract with the MCG Trust, the Australian Football League and the State Government. To finance the project, the State Government agreed to go guarantor for the Club’s borrowings of a sum up to but not exceeding $145 million.

Also fundamental to the financing of the project, however, was the need to secure a stream of revenue from corporate entertainment facilities. Early versions of the design of the new stand gave the best viewing position to the corporate boxes, but this design was vetoed by the then Premier, John Cain. Following discussions between the club, its architects and the Government, another tier of public seating was introduced over the line of corporate boxes, ensuring that the public had as good a view as the corporates. This change led to other amendments to the design, increasing the height and rake of the top tier.

The replacement of the old Southern Stand was an action which would fundamentally alter the presentation of the ground and the experience of large numbers of spectators. For most it represented a great improvement, but such a major change was not allowed to pass without comment. The replacement of the 1930s Southern Stand was opposed by a group of stalwarts calling themselves Saviors of the Southern Stand who by all accounts were desperate to save the old stand. More generally, there was a series of poignant commentaries on the demise of the infamous Bay 13. In December 1998, when the plan to replace the stand was officially announced, the Age mourned the loss of this particular part of the Outer, which it described as ‘rambuctious, noisy, impudent, often plain awful’, but …

you know how we have been searching these past ten years for the soul of Melbourne. There are real suspicions that it has been just a few yards back from the fence in Bay 13.

For once the Sun agreed, pointing out that in his autobiography, My Life in Cricket, champion bowler, Dennis Lillee had said that it was chanting from Bay 13 which spurred him on to break his world record of 310 test wickets.

Construction of the Great Southern Stand was undertaken by John Holland Constructions and commenced in mid-1990 and was completed in early 1992. The building accommodates 44,500 spectators and corporate clients, with more than 40,000 comfortably seated on four levels. Design features of note were many, including Anthony Pryor’s massive steel sculpture, ‘Legend’ positioned on the Brunton Avenue approach, the system of ramps within the building, the relative comfort of the seating, the efficacy of the services and catering systems and many others. The stand was officially opened on 16 March 1992 with the final of the World Cup, England v Pakistan. As Keith Dunstan notes, a billion people across 27 countries were watching as the MCG celebrated another significant milestone.

As a gesture to the new partnership between football and cricket, the four gates of the stand were named after some of the best known cricketers and footballers, the most famous of all batsmen, Don Bradman, champion footballer and triple Brownlow Medal winner, Dick Reynolds, cricketer and captain of the Australian team for the bodyline series of 1932-3, Bill Woodfall, and Syd Coventry, who captained the Collingwood Football Club to four successive premierships and won the Brownlow in 1927.

The Central Arena

Much of the following history and description of the central arena has been reproduced from the Melbourne Cricket Ground web site (http://www.mcg.org.au).

The MCG was first surveyed in 1861 by Melbourne Cricket Club committeeman Robert Bagot, who changed the ground's configuration into what is today's conventional oval. It previously was an irregular hexagon with a band rotunda in the northern corner. The arena remained virtually unchanged until 1955-56 when it was remodelled to international athletics specifications and a cinder track installed for the Olympic Games in November 1956. After the Games much of the arena was reconstructed and red mountain soil was laid to a depth of about 60cm. Compaction over the years gave this soil the consistency of clay and major drainage problems began to show up in the late 1980s. In the spring of 1992 the arena was completely reconstructed with a sand-based profile, giving the ground remarkable drainage characteristics and superior load-bearing ability.

Photographs indicate that the central arena has been encircled by a perimeter fence of a variety of types over the history of the ground, including post and rail, timber pickets and Victorian cast iron picket fence. It is assumed that these earlier fences were replaced in the course of the construction of new stands around the ground.MELBOURNE CRICKET GROUND - Assessment Against Criteria

Criterion A The historical importance, association with, or relationship to Victoria's history of the place or object.

The MCG is of historical and social significance for its long tradition of serving the people of Victoria, and for its reputation as 'the People's Ground'. It is also of historical significance as the pre-eminent venue for top-level cricket in Victoria and Australia since the mid to late nineteenth century and for its associations with the Melbourne Cricket Club, the oldest club in Victoria and a major force in the development of cricket and other sports in Victoria from the nineteenth century. The ground is also historically significant as the home of Australian Rules Football in Melbourne since the late nineteenth century and as the main venue for the 1956 Melbourne Olympics.

Criterion B The importance of a place or object in demonstrating rarity or uniqueness.

The MCG is the largest capacity and oldest stadium in the state and is unique in this context.

Criterion C The importance of a place or object in exhibiting the principal characteristics or the representative nature of a place or object as part of a class or type of places or objects.

This criterion is not relevant. In a state context, there are few grounds or stadia which are directly comparable to the Melbourne Cricket Ground.

Criterion D The place or object's potential to educate, illustrate or provide further scientific investigation in relation to Victoria's cultural heritage.

This criterion is not relevant.

Criterion E The importance of the place or object in exhibiting good design or aesthetic characteristics and/or in exhibiting a richness, diversity or unusual integration of features.

While the MCG is considered to be of limited architectural value and lacks the picturesque qualities associated with smaller, more traditional grounds, it is of considerable aesthetic power and significance at a state level for its overall form and scale. The MCG is a landmark on the edge of the city, a vast stadium which retains its traditional parkland setting. It is also of aesthetic significance for the tangible and intangible sensory experiences associated with the events which take place within.

Criterion F The importance of the place or object in demonstrating, or being associated with, scientific or technical innovations or achievements.

Ths criterion is not relevant. While the stands constructed at the Melbourne Cricket Ground in the post-World War II period typically have employed contemporary structural engineering technologies to achieve optimum design solutions, neither the ground nor its component parts are considered to meet this criterion at a state level.

Criterion G The importance of the place or object in demonstrating social or cultural associations.

MCG is of significance as a living icon, a focus of attention in the state and national contexts. Its social and cultural associations are numerous, relating not only to the long history of the place but also to its ongoing status as Victoria's pre-eminent sporting venue.

Criterion H Any other matter which the Heritage Council may consider relevant to the determination of cultural heritage significance.

Not applicable.MELBOURNE CRICKET GROUND - Permit Exemptions

General Exemptions:General exemptions apply to all places and objects included in the Victorian Heritage Register (VHR). General exemptions have been designed to allow everyday activities, maintenance and changes to your property, which don’t harm its cultural heritage significance, to proceed without the need to obtain approvals under the Heritage Act 2017.Places of worship: In some circumstances, you can alter a place of worship to accommodate religious practices without a permit, but you must notify the Executive Director of Heritage Victoria before you start the works or activities at least 20 business days before the works or activities are to commence.Subdivision/consolidation: Permit exemptions exist for some subdivisions and consolidations. If the subdivision or consolidation is in accordance with a planning permit granted under Part 4 of the Planning and Environment Act 1987 and the application for the planning permit was referred to the Executive Director of Heritage Victoria as a determining referral authority, a permit is not required.Specific exemptions may also apply to your registered place or object. If applicable, these are listed below. Specific exemptions are tailored to the conservation and management needs of an individual registered place or object and set out works and activities that are exempt from the requirements of a permit. Specific exemptions prevail if they conflict with general exemptions. Find out more about heritage permit exemptions here.Specific Exemptions:General Conditions:

1. All exempted alterations are to be planned and carried out in a manner which prevents damage to the fabric of the registered place or object.

2. Should it become apparent during further inspection or the carrying out of alterations that original or previously hidden or inaccessible details of the place or object are revealed which relate to the significance of the place or object, then the exemption covering such alteration shall cease and the Executive Director shall be notified as soon as possible.

3. If there is a conservation policy and plan approved by the Executive Director, all works shall be in accordance with it.

4. Nothing in this declaration prevents the Executive Director from amending or rescinding all or any of the permit exemptions.

5. Nothing in this declaration exempts owners or their agents from the responsibility to seek relevant planning or building permits from the responsible authority where applicable.

Specific Exemptions

The Melbourne Cricket Ground Reserve (outside stadium)

* All works or repair, maintenance or replacement of hard landscaping elements including gates, fencing, bollards, paving, kerbing, channels, seating, rubbish bins and other fixed and unfixed outdoor furniture.

* All removal, pruning and/or replacement of soft landscaping including grass, trees and general planting.

* Installation or replacement of any directional, statutory and other signage necessary for the management of the ground as a public sporting and entertainment venue.

* Installation, repair or replacement of all permanent or temporary services including power, gas, water, sewerage and telecommunications.

* Installation of signage to existing or new structures other than the Members Pavilion or the Great Southern Stand.

B1 Members Pavilion

Exterior, interior ground level concourse, members hall and main stair and Long Room including entry corridor and dining room:

*All repairs and maintenance that replace like with like or which restore or reconstruct original detailing and fabric.

* Painting of previously painted surfaces.

* Repair and/or replacement of stadium seating.

All other spaces:

* All non-structural works.

B2 Northern (Olympic) Stand

B3 Western (WH Ponsford) Stand

B4 Great Southern Stand

B5 Light Towers

* All works to the exterior and interior other than demolition works which impact on the original building structure.

Australian Gallery of Sport

* All works, including complete demolition, which do not increase the current building envelope.

Practice Wicket Area

*All works other than new buildings.

Oval and Fence

* All works other than the construction of any permanent structure or building.MELBOURNE CRICKET GROUND - Permit Exemption Policy

The document "Melbourne Cricket Ground Yarra Park, Jolimont, Conservation Management Plan" by Allom Lovell and Associates in association with Bryce Raworth, dated December 2000, forms a useful basis for understanding the development and significance of the MCG. In particular, Section 3.0 Analysis and Assessment of Significance and Section 4.0 Conservation Policy give good guidance as to the relative levels of significance of the component parts of the MCG and policies for their future treatment.

-

-

-

-

-

MOSSPENNOCH (MOSSPENNOCK)

Victorian Heritage Register H0420

Victorian Heritage Register H0420 -

BISHOPSCOURT

Victorian Heritage Register H0027

Victorian Heritage Register H0027 -

BRAEMAR

Victorian Heritage Register H0052

Victorian Heritage Register H0052

-

'YARROLA'

Boroondara City

Boroondara City -

1 Bradford Avenue

Boroondara City

Boroondara City

-

-

Notes See all notes

rohan storey • 03/10/16

In 2003-6, all these stands were demolished and replaced : B1 Members Pavilion B2 Northern (Olympic) Stand B3 Western (WH Ponsford) Stand, leaving only B4 Great Southern Stand, and the victorian era cast iron fence worthy of protection (and perhaps not the Great Southern Stand).

rohan storey • 03/10/16

In fac the cast iron fence isn't noted at all let alone as significant. A reappraisal of the Great Southern Stand might see it determined as an interesting blend of post-modern, high-tech and brutalist influences.

Public contributions

Notes See all notes

rohan storey • 03/10/16

In 2003-6, all these stands were demolished and replaced : B1 Members Pavilion B2 Northern (Olympic) Stand B3 Western (WH Ponsford) Stand, leaving only B4 Great Southern Stand, and the victorian era cast iron fence worthy of protection (and perhaps not the Great Southern Stand).

rohan storey • 03/10/16

In fac the cast iron fence isn't noted at all let alone as significant. A reappraisal of the Great Southern Stand might see it determined as an interesting blend of post-modern, high-tech and brutalist influences.