Back to search results

STATE GOVERNMENT OFFICES, GEELONG

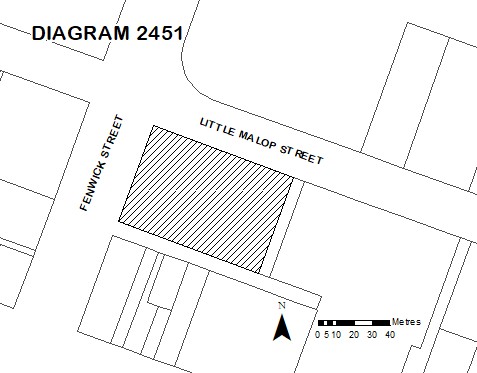

30 LITTLE MALOP STREET GEELONG, GREATER GEELONG CITY

STATE GOVERNMENT OFFICES, GEELONG

30 LITTLE MALOP STREET GEELONG, GREATER GEELONG CITY

All information on this page is maintained by Heritage Victoria.

Click below for their website and contact details.

Victorian Heritage Register

-

Add to tour

You must log in to do that.

-

Share

-

Shortlist place

You must log in to do that.

- Download report

2023 - north and east elevations

On this page:

Statement of Significance

What is significant?

The State Government Offices, Geelong, a six-storey Brutalist concrete building designed by the Public Works Department in conjunction with Buchan, Laird & Buchan in c.1974/75 and completed in 1978. It is popularly known as the ‘Upside-down building’ and has a highly distinctive form that resembles an upturned pyramid or ziggurat. This effect is produced by the progressively broader cantilevering of the upper floors and is emphasised by regularly repeating concrete spans. The setback allows for surrounding plazas on three sides. Vast areas of glazing contribute to its distinctive appearance and the provision of natural light and expansive views internally. The building was created to provide office accommodation for multiple government departments and agencies, and this use continues. The foyer contains a large mosaic mural by the then State Government artist Harold Freedman which is a finely produced work on an enormous scale. The mural’s content is characteristic of a mainstream 1970s view of Australian history and both its depiction of Aboriginal people and the nature of European colonisation are disrespectful by contemporary standards.

How is it significant?

The State Government Offices, Geelong, is of architectural significance to the State of Victoria. It satisfies the following criterion for inclusion in the Victorian Heritage Register:

Criterion D

Importance in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a class of cultural places and objects.

Criterion D

Importance in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a class of cultural places and objects.

Why is it significant?

The State Government Offices, Geelong, is architecturally significant as an important example of Brutalist architecture in Victoria. Its form, created by the cantilevering of upper levels, is highly dramatic and distinctive in Victoria. The building prominently displays several important aspects of the Brutalist approach – including an expressed structure and prominent use of concrete. Its fine design is complemented by the expansive mosaic mural by Harold Freedman in the building’s public foyer. Along with buildings such as the Moe Court House and the Footscray Psychiatric Centre, it is a defining work of the Public Works Department in the Brutalist style.

The building is also significant as a notable example of a twentieth-century State Government office. It is an unusually large and distinctive building of the type. Its scale, prominence and architectural boldness demonstrate the State Government’s enthusiasm for decentralising government services and jobs to regional centres in the 1970s.

(Criterion D)

The building is also significant as a notable example of a twentieth-century State Government office. It is an unusually large and distinctive building of the type. Its scale, prominence and architectural boldness demonstrate the State Government’s enthusiasm for decentralising government services and jobs to regional centres in the 1970s.

Show more

Show less

-

-

STATE GOVERNMENT OFFICES, GEELONG - History

Decentralisation and regionalisation

In the 1960s and 1970s, Federal, State and local governments actively pursued policies of decentralisation and regionalisation. In the 1960s, calls to grow regional cities and towns gathered momentum due to rapid growth in Australian capital cities and concerns about rural depopulation. In the 1970s, discussions about decentralisation began to focus on the relocation of manufacturing and service activities into non-metropolitan areas. Federally, the National Urban and Regional Development Authority was established and identified ten regional centres as proposed hubs for development, one being Geelong.[1] Geelong was particularly impacted by the scaling back of import tariffs in the early 1970s due to its reliance on auto manufacturing and related industries and unemployment emerged as a major concern.

The State Government’s decentralisation policy was aimed to ‘check the growth of metropolitan Melbourne and encourage the growth of country Victoria’.[2] As part of the policy, the government encouraged industry and businesses to relocate to regional centres via financial incentives and subsidies in an effort to boost employment. It also pursued the relocation of government jobs from metropolitan Melbourne to regional centres. Although the State Government had maintained offices in regional centres since the early twentieth century, the 1970s saw a concerted effort to shift departments and agencies from Melbourne to centres like Geelong. Concurrently, the Victorian Public Offices Corporation was established with the aim of reducing the State Government’s reliance on rented premises. During construction, the Geelong State Government Offices was promoted as the first major new building to be commenced under the policy. On its opening, the project was celebrated as the most substantial of the new regional State Government offices completed under the decentralisation policy, with Premier Hamer commenting that ‘I know of no matching comprehensive centre in a regional centre in Australia’.[3]

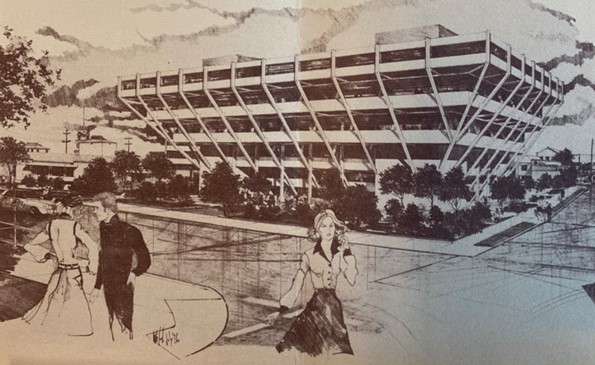

Building design and construction

Calls for a major new State Government office building in Geelong are evident from the late 1960s. The local council pressed for the transfer of government departments from Melbourne to Geelong and for the construction of a new office to be expedited.[4] A commitment to commence the project was made during the 1973 election campaign.[5] The design for the State Government Offices appears to have been completed by the Public Works Department by mid-1975. Premier Rupert Hamer announced that construction would begin on the Geelong State Government Offices in February 1976.[6] Documentation for the building was carried out by the architectural firm Buchan, Laird & Buchan in association with engineers W. L. Meinhardt and Partners.[7] Buchan, Laird & Buchan, which was rebadged as Buchan, Laird & Bawden shortly after the building’s completion, was a prolific architectural practice established in Geelong in 1890. After World War II, the firm expanded to take on an array of major commercial, industrial and government projects in Victoria and beyond, including several shopping centres, major buildings for Shell, the Ford administration building in Broadmeadows (1964), and the AMP building in Geelong (1970). [8]

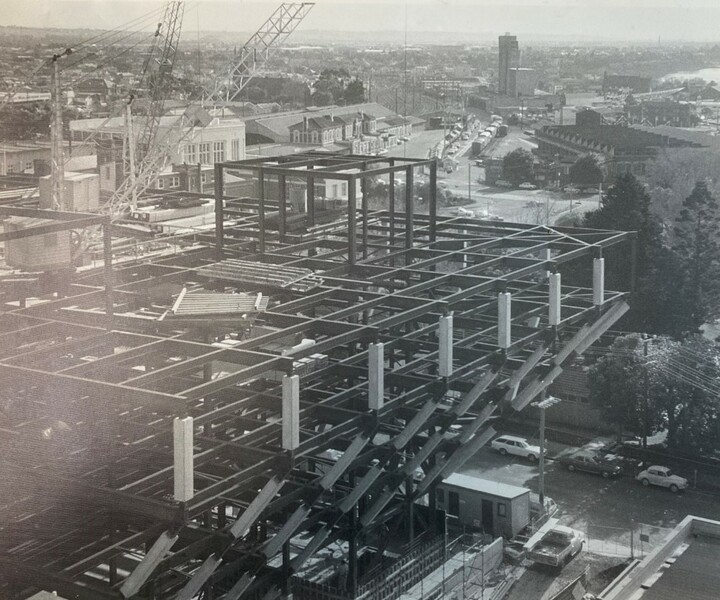

The builders, J. C Taylor, were awarded the contract for the building’s construction amid controversy about the lack of a tendering process. Construction began on the State Government Offices in May 1976. Economic inflation had a significant impact on the cost of the project. The Geelong News reported that at the ceremony marking the commencement of construction in August 1976, it was stated the cost of the building would be $8.5 million. Two months later, the director of building contractors was unable to estimate the final cost of the project due to the rate of inflation.[9]

The steel framework for the building was well advanced by early 1977, and construction appears to have been completed by late 1978 when the first government tenants moved into the building. [10] The building was officially opened by Premier Rupert Hamer on 20 March 1979.[11] The building was designed to accommodate up to 700 public servants across 22 government departments and agencies, including VicRail, the Public Trustee and the Workers Compensation Board. The building originally contained a staff cafeteria and caretaker's flat on the fifth floor. In reviewing the building, architect and critic Norman Day was somewhat amused by the building but concluded that ‘[t]he building is a good one. It’s gutsy and almost unavoidable…[t]he powerful structure is not loosened by ornament or a mixture of materials. It is formal, clean and simple.’[12] It was nominated in the new building category of the Victorian chapter of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects awards in 1979. Its distinctive architecture has received attention in recent years. It was profiled among just 20 examples of Brutalist architecture in Australia in the Phaidon Atlas of Brutalist Architecture, published in 2020. The building continues to be used as offices for an array of Victorian Government departments and agencies.

Brutalism

An architectural approach that has come to be known as Brutalism emerged from various forces within European architecture in the mid-twentieth century. Particularly emblematic of post-war Britain, Brutalist buildings were typically assertive, featured powerful, blocky forms and were honest in their use of materials and form of construction. They were often the expression of civic intentions of the post-war welfare state and became particularly associated with the provision of public housing and government buildings. A worldwide phenomenon, Brutalist architecture first appeared in Australia in the 1960s. It was a robust and highly adaptable style suited to institutional buildings, and some of the first examples appeared at university campuses. In Victoria, influential architects Kevin Borland, Graeme Gunn, Evan Walker, and Daryl Jackson adopted the style for major commissions from the late 1960s. Borland and Jackson produced the notable Brutalist design for the Harold Holt Memorial Swimming Centre (VHR H0069), constructed in 1969. During the early 1970s, Brutalism became the style of choice for the union movement, as evidenced by the Plumbers and Gasfitters Union Building (VHR H2307) and Clyde Cameron College (VHR H2192). Brutalism also became influential within the Victorian Public Works Department in the 1970s. During this period, the Department produced buildings that explored various versions of the style, including the fortress-like Footscray Psychiatric Centre (VHR H2395, completed 1976) and the more playful and expressive Moe Courthouse (VHR H2432, completed 1979). Although the popularity of Brutalism diminished through the 1980s, it is now considered a key architectural style of the twentieth century.

Mosaic mural

In 1972, the State Government appointed Harold Freedman (1915-99) as State Artist and developed a studio of State Art with the aim of producing public murals to document themes in Victoria’s history. The History of Transport Mural for the main concourse of Spencer Street Railway Station unveiled in 1978, was the first to be completed. The expansive painted mural was included in the VHR in 2001 (VHR H1936). It was decided in 1976 that the new major regional government offices should contain murals by the State Artist depicting the region’s history.[13] There was, however, debate between Freedman and the building’s architects about the placement of the mural, which Freedman had envisioned would be on the exterior. A mosaic mural for the foyer portraying a regional history of Geelong was the negotiated outcome. It took over two years and nearly two tons of glass tesserae to complete.[14] Mosaic was chosen as the medium for the mural due to its durability, as the mural was to be located in a publicly accessible foyer space.[15] Research for the mural was carried out by CSIRO scientist Dr Roy Lang, and assistance was provided by David Jack, Joseph Attard, Antonio Barrese and Heather Steele. The mural was produced from 1978 and unveiled in 1980. The 30-metre long mural remains in place in the foyer of the State Government Offices in Geelong. It depicts a late twentieth-century mainstream view of the history of the region. Both its depiction of Aboriginal people and the nature of colonisation are disrespectful by today’s standards.

Newspapers and primary sourcesDay, Norman., The Age, 27 March 1979.

Premier Hamer speaking notes, Official Opening of the Geelong State Government Offices, 20 March 1979.

Public Works Department brochure, Official Opening of the Geelong State Government Offices.

Govt. Offices – May Start’, Geelong Advertiser, 24 February 1976.

Geelong Advertiser, April 16 1977.

Websites and social media

Books

Buchan Laird & Buchan Pty Ltd, 90 Years of Architecture, 1980.

Freedman, Harold., A Regional History: The Story Told in Glass, 1980.

Fry, Gavin; Freedman, David & Jack, David; Harold Freedman: The Big Picture, Melbourne Mural Studio, 2017.

Goad, Philip and Willis, Julie (eds). The Encyclopedia of Australian Architecture, Cambridge University Press, Port Melbourne, 2012.

McLeod, Virginia, and Emma Barton, eds. Atlas of Brutalist Architecture, London: Phaidon Press, 2020.

Page, Michael., An architectural apex, Buchan Laird International, South Yarra.

[1] State & Local Government Review, Vol. 10, No. 1, January 1978, pp. 35-38.

[2] Official Opening of the Geelong State Government Offices 20 March 1979 PROV 3743/P0000.

[3] Official Opening of the Geelong State Government Offices 20 March 1979 PROV 3743/P0000.

[4] ‘State Offices Start Here by June’, The News, 3 August 1973.

[5] John Jost, ‘Special Report: Geelong – Government office deal’, undated.

[6] ‘Govt. Offices – May Start’, Geelong Advertiser, 24 February 1976.

[7] Public Works Department Victoria (brochure), Official Opening of the State Government Offices Geelong.

[8] Philip Goad and Julie Willis (eds), The Encyclopedia of Australian Architecture, Cambridge University Press, 2012, p. 111; Michael Page, An Architectural Apex, Buchan Laird International, South Yarra, p. 164.

[9] An Architectural Apex.

[10] Geelong Advertiser, April 16 1977.

[11] Public Works Department Victoria (brochure), Official Opening of the State Government Offices Geelong; Geelong Advertiser, 21 March 1979.

[12] Norman Day, The Age, 27 March 1979.

[13] Gavin Fry, David Freedman & David Jack, Harold Freedman: The Big Picture, Melbourne Mural Studio, 2017.

[14] Harold Freedman, A Regional History: the Story Told in Glass, 1980.

[15] A Regional History: the Story told in Glass.STATE GOVERNMENT OFFICES, GEELONG - Permit Exemptions

General Exemptions:General exemptions apply to all places and objects included in the Victorian Heritage Register (VHR). General exemptions have been designed to allow everyday activities, maintenance and changes to your property, which don’t harm its cultural heritage significance, to proceed without the need to obtain approvals under the Heritage Act 2017.Places of worship: In some circumstances, you can alter a place of worship to accommodate religious practices without a permit, but you must notify the Executive Director of Heritage Victoria before you start the works or activities at least 20 business days before the works or activities are to commence.Subdivision/consolidation: Permit exemptions exist for some subdivisions and consolidations. If the subdivision or consolidation is in accordance with a planning permit granted under Part 4 of the Planning and Environment Act 1987 and the application for the planning permit was referred to the Executive Director of Heritage Victoria as a determining referral authority, a permit is not required.Specific exemptions may also apply to your registered place or object. If applicable, these are listed below. Specific exemptions are tailored to the conservation and management needs of an individual registered place or object and set out works and activities that are exempt from the requirements of a permit. Specific exemptions prevail if they conflict with general exemptions. Find out more about heritage permit exemptions here.Specific Exemptions:

The works and activities below are not considered to cause harm to the cultural heritage significance of the State Government Offices, Geelong subject to the following guidelines and conditions:

Guidelines

1. Where there is an inconsistency between permit exemptions specific to the registered place or object (‘specific exemptions’) established in accordance with either section 49(3) or section 92(3) of the Act and general exemptions established in accordance with section 92(1) of the Act specific exemptions will prevail to the extent of any inconsistency.

2. In specific exemptions, words have the same meaning as in the Act, unless otherwise indicated. Where there is an inconsistency between specific exemptions and the Act, the Act will prevail to the extent of any inconsistency.

3. Nothing in specific exemptions obviates the responsibility of a proponent to obtain the consent of the owner of the registered place or object, or if the registered place or object is situated on Crown Land the land manager as defined in the Crown Land (Reserves) Act 1978, prior to undertaking works or activities in accordance with specific exemptions.

4. If a Cultural Heritage Management Plan in accordance with the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006 is required for works covered by specific exemptions, specific exemptions will apply only if the Cultural Heritage Management Plan has been approved prior to works or activities commencing. Where there is an inconsistency between specific exemptions and a Cultural Heritage Management Plan for the relevant works and activities, Heritage Victoria must be contacted for advice on the appropriate approval pathway.

5. Specific exemptions do not constitute approvals, authorisations or exemptions under any other legislation, Local Government, State Government or Commonwealth Government requirements, including but not limited to the Planning and Environment Act 1987, the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006, and the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth). Nothing in this declaration exempts owners or their agents from the responsibility to obtain relevant planning, building or environmental approvals from the responsible authority where applicable.

6. Care should be taken when working with heritage buildings and objects, as historic fabric may contain dangerous and poisonous materials (for example lead paint and asbestos). Appropriate personal protective equipment should be worn at all times. If you are unsure, seek advice from a qualified heritage architect, heritage consultant or local Council heritage advisor.

7. The presence of unsafe materials (for example asbestos, lead paint etc) at a registered place or object does not automatically exempt remedial works or activities in accordance with this category. Approvals under Part 5 of the Act must be obtained to undertake works or activities that are not expressly exempted by the below specific exemptions.

8. All works should be informed by a Conservation Management Plan prepared for the place or object. The Executive Director is not bound by any Conservation Management Plan and permits still must be obtained for works suggested in any Conservation Management Plan.

Conditions

1. All works or activities permitted under specific exemptions must be planned and carried out in a manner which prevents harm to the registered place or object. Harm includes moving, removing or damaging any part of the registered place or object that contributes to its cultural heritage significance.

2. If during the carrying out of works or activities in accordance with specific exemptions original or previously hidden or inaccessible details of the registered place are revealed relating to its cultural heritage significance, including but not limited to historical archaeological remains, such as features, deposits or artefacts, then works must cease and Heritage Victoria notified as soon as possible.

3. If during the carrying out of works or activities in accordance with specific exemptions any Aboriginal cultural heritage is discovered or exposed at any time, all works must cease and the Secretary (as defined in the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006) must be contacted immediately to ascertain requirements under the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006.

4. If during the carrying out of works or activities in accordance with specific exemptions any munitions or other potentially explosive artefacts are discovered, Victoria Police is to be immediately alerted and the site is to be immediately cleared of all personnel.

5. If during the carrying out of works or activities in accordance with specific exemptions any suspected human remains are found the works or activities must cease. The remains must be left in place and protected from harm or damage. Victoria Police and the State Coroner’s Office must be notified immediately. If there are reasonable grounds to believe that the remains are Aboriginal, the State Emergency Control Centre must be immediately notified on 1300 888 544, and, as required under s.17(3)(b) of the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006, all details about the location and nature of the human remains must be provided to the Secretary (as defined in the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006.

Exterior

1. Removal of modern canopy over main entrance.2. Replacement of damaged glazing with a product that matches the appearance of the existing glazing.3. All works to the roof that do not alter the visual appearance of the building from street level.

Interior

Basement

4. All non-structural works contained within the basement.

Ground floor

5. All works to areas beyond the main public foyer and lift lobbies.6. All works to amenities areas.7. All works to the security desk in the public foyer, including removal.8. Maintenance, repair, replacement and installation of services within the public foyer.9. Maintenance, repair, removal and replacement of fixed signage in existing locations in the public foyer. This does not apply to the commemorative plaques at the east end of the foyer.10. Removal of modern accretions to originally exposed concrete elements in the public foyer.First – Fifth floor

11. All non-structural works that do not cover, alter or involve insertions into concrete columns, internal walls of bush-hammered concrete and concrete finish to lift lobbies.12. Removal of overpainting and modern accretions to originally exposed concrete elements.

STATE GOVERNMENT OFFICES, GEELONG - Permit Exemption Policy

1. It is recommended that a Conservation Management Plan is prepared for the place and that it is used to guide the future management of the place.2. It is recognised that the cultural heritage significance of the place lies largely in its exterior architecture and the dramatic form on its northern, eastern and western elevations. Efforts should be made to maintain the exterior appearance of the building and the plazas to the north and west as they appear from street level.3. The interiors of the building are generally not noteworthy. The basement has no significant features. On ground level, the open aspect of the foyer is important and the mural is a significant feature, as are plaques and areas of exposed concrete. All other floors have been modernised over time. Although there are some original significant fabric to these floors that should be retained and conserved, such as areas of exposed concrete, there is capacity for non-structural change to the interior on these levels. Unimpeded views from the interior outwards are an important feature of the place.4. Where concrete finishes that were originally exposed have been overpainted or covered with additional modern material, their uncovering is supported.5. It is recognised that the mural in the foyer is both an artwork on an impressive scale by an accomplished artist and a representation of history that is disrespectful to Aboriginal people. It is suggested that any proposed change to the mural or its surrounds is best carried out through a permit process that enables these complexities to be properly explored and addressed.

-

-

-

-

-

FORMER GEELONG WOOL EXCHANGE

Victorian Heritage Register H0622

Victorian Heritage Register H0622 -

FORMER SCOTTISH CHIEFS HOTEL

Victorian Heritage Register H0662

Victorian Heritage Register H0662 -

GEELONG TOWN HALL

Victorian Heritage Register H0184

Victorian Heritage Register H0184

-

ACTOR'S STUDIO HOUSE

Victorian Heritage Register H2420

Victorian Heritage Register H2420 -

ANZ BANK (FORMER)

Ballarat City H114

Ballarat City H114

-

-