STANHILL

33-34 QUEENS ROAD MELBOURNE, PORT PHILLIP CITY

-

Add to tour

You must log in to do that.

-

Share

-

Shortlist place

You must log in to do that.

- Download report

Statement of Significance

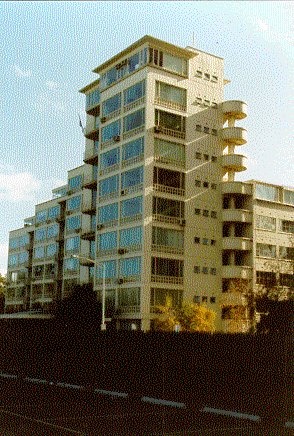

Stanhill is a nine storey block of flats in South Melbourne, designed in an inter-war Functionalist style by renowned emigre architect Frederick Romberg. Considered to be the most impressive of his works, it was designed in 1942 but not completed until 1950.

The flats are of finely executed off-form concrete construction with sophisticated steel and glass detailing. The building is asymmetrically massed with stepped plan and elevation. The southern facade is of concrete frame containing large areas of flush glazing, with individual thin slab balconies and slim iron railings. Four main masses are stepped back at a slight angle to allow privacy and to give views to all. The northern facade is strikingly different, with a broad and fluid sweep of open access galleries shading glazing to cill height . The galleries are connected to a closed stairway at the Queens Road end, to the central lift tower, and to the sculpted open stairway at the eastern end. The roof sports attic flats and roof gardens, stepped down towards Albert Park. The building is in excellent condition, though altered internally to accommodate professional suites since the 1970s. The mature Chilean Wine Palm near the south east corner of the building predates Stanhill and has become a landmark of the site.

How is it significant?

Stanhill is of architectural, historic, and aesthetic significance.

Why is it significant?

Stanhill is architecturally and aesthetically significant as the most ambitious and accomplished project by the renowned emigre architect Frederick Romberg. The design of Stanhill is a rigorous and coherent application of Functionalist principles, combined with Romberg's individualistic interpretation. Stanhill stands apart from more derivative Internationalist compositions by many other architects of the time and subsequently.

Stanhill is of historical significance for its ability to illustrate the high point of a cosmopolitan and metropolitan direction in urban dwelling styles in large Australian cities mid-century. Stanhill is a leading and innovative example of the few large scale and tall luxury flat developments built in the Melbourne in the mid twentieth century, and the first tall residential development on St Kilda Road. Stanhill marked the end of a trajectory in flat developments prior to a turn to the suburban dreaming and the social engineering of state housing projects.

Stanhill demonstrates outstanding quality in integrated design and construction for its period, consummately incorporating fluid forms and smooth and fluted finishes in off form concrete, as well as closely allied and subtle detailing in glass and steel window framing.

-

-

STANHILL - History

Contextual History:

Frederick Romberg was born in China and grew up in Berlin. As a youth in Hamburg, Romberg had contact with expressionist architects. His law studies were interrupted when he fled from Nazi authorities to Switzerland. In Zurich he was persuaded to study architecture, and was taught by Gropius, whom he admired, and Mendelsohn, whom he did not. He identified most strongly with the Swiss Heimatsil architects, who "distrusted bold architectural gestures, and who concentrated on technical virtuosity, both in construction and in the details of their buildings". These attributes were highly developed in Romberg’s work, but he did not confine himself to the particular palette that the Heimatsil preferred. In Switzerland he came into contact with the use of off-form concrete, which he used to great effect in both Newburn and Stanhill.

Romberg’s thesis won him a travelling scholarship, but he stayed and worked for a while for the functionalist architect Savilsberg, before coming to Australia. On his arrival, Romberg worked for Stephenson & Turner for several years, contributing substantially to projects such as the Australian Pavilion of the New York World Fair of 1939, and another exhibit for an exposition in Auckland.

Romberg’s first independent building was Newburn, at 30 Queens Road, which is currently on the HBC register. It made groundbreaking use of off-form concrete and made allusions to Gropius’s Berlin housing estate of 1930. The design was compromised in a number of ways - the number of storeys were reduced, the rising on pilotis was eliminated, and instead of the uniform saw-tooth Romberg wanted, the front flats were turned straight on to Queens Road and the access tower moved back between these and the other flats. Johnson states that "Newburn was solid design for the period, while Grounds flats were rather more prophetic". The same could be said for Stanhill.

Romberg teamed up with Mary Turner Shaw who he had worked with at Stephenson and Turner. This partnership produced Glenunga in Armadale and Yarabee in South Yarra, both small-medium scale but significant apartment blocks. Glenunga used a number of Heimatsil elements, and was criticised by Boyd as cluttered. Romberg then set off on his own, and during this period, around 1942, he designed Stanhill for the clients Stanley and Hillary Korman. Building did not commence for six years, and Stanhill was completed was in 1950.

It is important to establish Romberg's position in relation to the architectural styles being practised in Australia at this time. Most commentators on the development of modernist architecture in Australia in the inter-war period acknowledge that there was a strong element of superficiality in the adoption of the various styles coming from Europe. As Donald Leslie Johnson puts it, ".. there was no reason for Australia to promote an architecture to meet whatever new pragmatic or philosophic ideals which might have existed [in Europe]. Therefore, stylistic changes were to a very large degree a matter of taste". It is Romberg’s, and Stanhill’s departure from this paradigm that sets them apart.

Stanhill (and Newburn) are often compared to the works of Stephenson and Turner, particularly their hospitals. While there is a strong resemblance in the elements used, and in scale, critics have argued that the respective styles are substantially different. Stephenson and Turner’s works are generally categorised as being ‘functional expressionist’, a variety of ‘international’ style connected with the later work of Mendelsohn. Hamann asserts that "Stanhill is linked visually with buildings from the early streamlined phase of modernism, in particular with the Stephenson and Meldrum hospitals of the mid-thirties. But a closer look reveals that Stanhill is a completely new kind of architecture". Hamann’s thesis is that Romberg’s product was evolutionary, truly functionalist, and deviated from the "contrived, stylised asymmetry" of ‘functional expressionist’ architecture, which came to dominate large buildings in Australia in the 1930s. Romberg’s use of concrete in Stanhill was fluid, as opposed to the simple rectilinear elements favoured by the International stylists.

In terms of the practicalities of the building programme, large blocks of flats with compact plans created difficult access problems. The open access way had been abandoned as undesirable in earlier suburban flats, but was revived as a simple solution by modernists who considered such forms of circulation desirable and superior. While Stanhill provided private balconies, it gave limited communal outdoor space, apart from the roof top gardens. The principle adhered to was the modernist one of using a compact plan and giving more open space at ground level.

Stanhill is notable for its particular statement about high rise living as well as for its design and styling. The demand for inner city medium to high density dwellings, and the architectural determinism of the modernists were a complex mix. Romberg hoped that Stanhill would be a step on the way to providing compact and modern housing for all economic groups. His design of 1946 for the Gloucester Flats, a project of bachelor flats of even larger scale than Stanhill, was intended to address this need, but was never built. Parallels are made between Stanhill and J.W. Rivett’s flats in Tahara Road, Toorak, and A.M. Bolot’s later flats at Potts Point Sydney, 1948.

Stanhill was at the end of an architectural trajectory made possible by fashion in dwelling aspirations of the affluent. Social changes were to render such an approach unpopular up to the present, when the demographic once again has created a space for a choice of stylish apartment living. In the late forties the few blocks of high rise flats became novelties as the emphasis for both architects and shifted to the detached house and garden - the suburban dream. The next major exercises in high density living were the government high rises of the late fifties, using prefabricated concrete panel construction. Romberg’s work had some influence on the schemes adopted by the government architects. Interestingly Romberg opposed the use of these high density high rises as a ‘solution’ to the problems of slums - in this situation he advocated row housing. Stanhill has most resonance as a precursor of the types of inner city housing being built today.

Romberg’s next large housing project, Hilstan (now demolished), while displaying a trace of the fluidity of earlier works, was low rise and returned to "unassuming construction with brick and wood, restricting concrete to flooring and some minor cantilevering". In Hilstan, Romberg fused past and present forms, as Grounds had done.

Romberg’s later influence in the post-war period was linked to his partnership with Grounds and Boyd, and his University appointments. In the late 1950s he completed many large commercial works, making use of his talent with concrete, steel and glass, and even pioneering some aspects of Brutalism.

Hamann argues that in the 1960s the focus in architecture moved to Sydney, to Seidler, and to the pursuit of structural virtuosity and tallness. The modernism of "creativity and rigorous assessment of design" was left behind. Romberg belatedly received the RAIA Presidents award in 1983 for his past, present and future service to Architecture and the Community in Victoria.

History of Place:

St Kilda Road had been a boulevard of expansive mansions, but in the 1930s and 40s the area attracted a number of privately developed blocks of flats, mostly of a medium scale, for relatively wealthy residents who wished to emulate European models of city living. A number of these blocks of flats, including Brookwood, still exist today on Queen Street, lending context to Stanhill.

Romberg supervised the construction of Stanhill from his roof-top studio in Newburn, where he could see the works in progress. The strong reactions to the building indicate its relevance as a document of the mentalite of a period. A negative reaction, by the unions among others, concerned the large scale use of steel windows frames and large panes of glass, which were materials in short supply in the post war period, for such a luxury purpose, when the common people who had pulled together in the war needed them for their suburban dwellings. The architectural reactions included complaints that Stanhill was "an exaggerated and unorganised jumble and a monumental incubator". Yet Stanhill excited interest amongst overseas architects.

Romberg and Boyd's office designed modifications for Stanhillin 1967 bu these were not undertaken. In the 1970s, as a result of changing demographics in the area, Stanhill was adapted for commercial use. It has proved well suited to use for professional suites, as some of the requirements for accessibility yet privacy, domestic scale and discretion, as well as prestigious address, are similar to that envisaged in the original use as flats. There has been a strong identification with Stanhill by architects and designers, several of whom have their offices there. This could perhaps be seen as an antipodean version of the popularity of Corbusier’s ‘Unite d’Habitation’ and Pessac flats. In a sense, Stanhill has been adopted as an icon of a golden age of modernism.

Along with these changes went upgrading of services, including adaptation for an up to date fire rating. Changes have been made to attic overhangs, to access way paving, internal alterations to flats and linking of flats, and painting and patching of the concrete. The planning of the interiors of the flats is not the focus of most commentators and the loss of some of these details does not compromise the values that make this work significant - Stanhill still reads as a block of flats. The overall effect, the original architectural intent and expression, are still largely available for interpretation.

Associated People: A series of well known and frequently exhibited photographs of Stanhill from the 1950s by noted emigre photographer Wolfgang Sievers is held by the National Library.

First owner Stanley KormanSTANHILL - Assessment Against Criteria

Criterion A

The historical importance, association with or relationship to Victoria's history of the place or object.Criterion B

The importance of a place or object in demonstrating rarity or uniqueness.Criterion C

The place or object's potential to educate, illustrate or provide further scientific investigation in relation to Victoria's cultural heritage.Criterion D

The importance of a place or object in exhibiting the principal characteristics or the representative nature of a place or object as part of a class or type of places or objects.Criterion E

The importance of the place or object in exhibiting good design or aesthetic characteristics and/or in exhibiting a richness, diversity or unusual integration of features.Criterion F

The importance of the place or object in demonstrating or being associated with scientific or technical innovations or achievements.Criterion G

The importance of the place or object in demonstrating social or cultural associations.Criterion H

Any other matter which the Council considers relevant to the determination of cultural heritage significanceSTANHILL - Permit Exemptions

General Exemptions:General exemptions apply to all places and objects included in the Victorian Heritage Register (VHR). General exemptions have been designed to allow everyday activities, maintenance and changes to your property, which don’t harm its cultural heritage significance, to proceed without the need to obtain approvals under the Heritage Act 2017.Places of worship: In some circumstances, you can alter a place of worship to accommodate religious practices without a permit, but you must notify the Executive Director of Heritage Victoria before you start the works or activities at least 20 business days before the works or activities are to commence.Subdivision/consolidation: Permit exemptions exist for some subdivisions and consolidations. If the subdivision or consolidation is in accordance with a planning permit granted under Part 4 of the Planning and Environment Act 1987 and the application for the planning permit was referred to the Executive Director of Heritage Victoria as a determining referral authority, a permit is not required.Specific exemptions may also apply to your registered place or object. If applicable, these are listed below. Specific exemptions are tailored to the conservation and management needs of an individual registered place or object and set out works and activities that are exempt from the requirements of a permit. Specific exemptions prevail if they conflict with general exemptions. Find out more about heritage permit exemptions here.Specific Exemptions:

General Conditions:1. All alterations are to be planned and carried out in a manner which prevents damage to the fabric of the registered place or object.

2. Should it become apparent during further inspection or the carrying out of alterations that original or previously hidden or inaccessible details of the place or object are revealed which relate to the significance of the place or object, then the exemption covering such alteration shall cease and the Executive Director shall be notified as soon as possible.

3. If there is a conservation policy and plan approved by the Executive Director, all works shall be in accordance with it.

4. Nothing in this declaration prevents the Executive Director from amending or rescinding all or any of the permit exemptions.

Nothing in this declaration exempts owners or their agents from the responsibility to seek relevant planning or building permits from the responsible authority where applicable.

Building exterior

* Maintenance and repairs which replace like with like* Removal of extraneous items such as, pipe work, ducting, wiring, antennae, aerials etc, and making good.* Regular garden maintenance* Installation, removal or replacement of garden watering systems

Public internal spaces

* Installation of smoke detectors and emergency exit signs* Repainting in existing or original colours* Replacement of light fittings in existing positions with similar type* Replacement of floor coverings to lift lobbies above the ground floor* Changes to the lift car interior

Windows

* Replacement of large balcony windows when necessary with two panes of glass with a siliconed central vertical joint

Interiors of units

* Painting

* Installation, removal or replacement of carpets and/or flexible floor coverings.* Installation, removal or replacement of curtain track, rods, blinds and other window dressings.* Installation, removal or replacement of hooks, nails and other devices for the hanging of mirrors, paintings and other wall mounted artworks.* Refurbishment of bathrooms, toilets and or en suites including removal, installation or replacement of sanitary fixtures and associated piping, mirrors, wall and floor coverings.* Installation, removal or replacement of kitchen benches and fixtures including sinks, stoves, ovens, refrigerators, dishwashers etc and associated plumbing and wiring.* Installation, removal or replacement of hydronic or radiant type heating provided that the installation does not damage existing skirtings and architraves.* Installation, removal or replacement of electrical wiring provided that all new wiring is fully concealed.* Installation of smoke detectors and emergency exit signs* Installation in flats of internal partitions subject to the following conditions:(a) Partitions shall not abut windows.

(b) Partitions normal to windows must stop short of the window the full depth of the original sill, or at the face of the wall below the sill, which-ever is further so as to maintain the external appearance of the glazing. The space between the ends of partitions and windows may be filled with a single thickness of glass. If sealed at the junction with the window a transparent sealant must be used.(c) Fixings for partitions are to of a type which do not damage the finished surfaces of columns and beams, or the heating coils in the floors/ceilings.(d) Remaining original sliding partitions between living room and bedroom are to be retained.STANHILL - Permit Exemption Policy

ADDITIONAL BUILDINGS

Further building on the site should be strictly limited.

EXISTING NON REGISTERED BUILDINGS

The three storey flat building on the north side of the site is not considered significant at a State level, and so is not itemised in the extent of registration. However, major external alteration or addition to this building which would impact negatively on the setting of Stanhill would be subject to the permit process.

Alterations to the existing concrete car park to the north including security fencing and junctions with the building which lessen its negative effect will be permitted. Relocation of exposed services plant from the entrance of the car park to a less obtrusive position would also be permitted.

LANDSCAPE

The garden on the south and west sides should remain formal but low key and low height. The mature Chilean Wine Palm is to be retained.

BUILDING EXTERIOR

The continuity and uniformity of the original external architectural features, patterns and details of the facades, balconies, windows and doors should be retained.

Accurate reinstatement of original features such as the southern attic over hangs or the northern pergolas to the penthouses west of the lift-well will be encouraged.

Further additions to rooftop and penthouse areas should be limited so as to maintain the stepped skyline of the building. The provision of new shading devices and increases in accessible balcony areas to rooftop spaces and balconies of penthouses should be limited. [Past additions such as the ninth floor flat on the south side will not be considered as a precedent to allow further rooftop additions or extensions.]

AIR CONDITIONERS

Removal of older inappropriate air conditioning vents is encouraged.

The installation of air conditioning plant with low visual impact such as split systems will be viewed favourably if the visual and fabric impact is kept low. [With split systems the external plant can be placed on a balcony and small scale ducting led to internal plant. The external portion of a split system on balconies should be installed onthe slab,with its length against a wall and away from balustrades, and with minimal visible ducting.]

PUBLIC INTERNAL SPACES ? LIFT FOYERS AND ACCESS GALLERIES

The layout of the spaces and the wall and the ceiling finishes of the lift lobbies and access galleries should be maintained. The lift doors and surrounds should be retained. Return of the car interiors to their original design would be supported.

Doorways from units opening directly into the lift lobby spaces will be supported where they open into the narrower alcoves between the main lift lobby space and the doors to the galleries and where the doors are plain.

WINDOWS

Windows are the dominant architectural element of the southern facade, and make an important contribution to the composition of the other facades. Little room exists for alteration without negative impact on significance. A number of elements are essential to the integrity of the window system including the steel frames and fittings/furniture, and on the south side the wide sills, coved pelmet above, the flaring columns and lighting of the penthouses. The gridded concrete glazing bar system to chair rail height is vital to the composition of the facade. Removal of air-conditioning units from window grids would be approved on condition that the grid was properly restored at the same time.

Replacement and repair of steel frame windows should use closely matched sections and maintain the appearance of the original. The gridded glazing in side lights to doorways to the north side galleries should be maintained and replacements should be undertaken in similar materials and pattern to the original. The large balcony window-panes of the south facade can be replaced when necessary with two panes with a vertical silicone joint between.

INTERIORS OF FLATS

The original layouts and fit-outs of the flats make an important contribution to the building's significance.

The plain primary surfaces and finishes of the original apartment interiors, in particular, the smooth hard plastered ceilings, the similarly plastered reinforced concrete beams and columns with quad moulded arrises and the related large timber half round moulding of the original door architraves.

PENTHOUSE INTERIORS

The flaring columns and associated lighting fixtures should be retained clear of internal partitioning. The transparency of the continuous windows and glazed doors should be maintained with internal partitioning being avoided.

Original built in wardrobes should be retained.

Suspended or directly applied new ceilings would be permissible on condition that they are reversible. [Nail or impact fastening would not be permitted as it leads to spalling on removal and may puncture original in floor hot water heating pipes.]

The installation of single connecting doors between the flats is supported on condition that suitable detailing of doors, architraves, door size and head height are applied.

-

-

-

-

-

MAJELLA

Victorian Heritage Register H0783

Victorian Heritage Register H0783 -

NEWBURN FLATS

Victorian Heritage Register H0578

Victorian Heritage Register H0578 -

RATHGAEL - THE WILLOWS

Victorian Heritage Register H0096

Victorian Heritage Register H0096

-

"1890"

Yarra City

Yarra City -

"AMF Officers" Shed

Moorabool Shire

Moorabool Shire -

"AQUA PROFONDA" SIGN, FITZROY POOL

Victorian Heritage Register H1687

Victorian Heritage Register H1687

-

Anunaka Mansion

Casey City

Casey City -

Axedale Hall

Greater Bendigo City

Greater Bendigo City -

BEAUFORT HOUSE

Merri-bek City

Merri-bek City

-

-