Back to search results

FAIRFIELD PARK AMPHITHEATRE COMPLEX

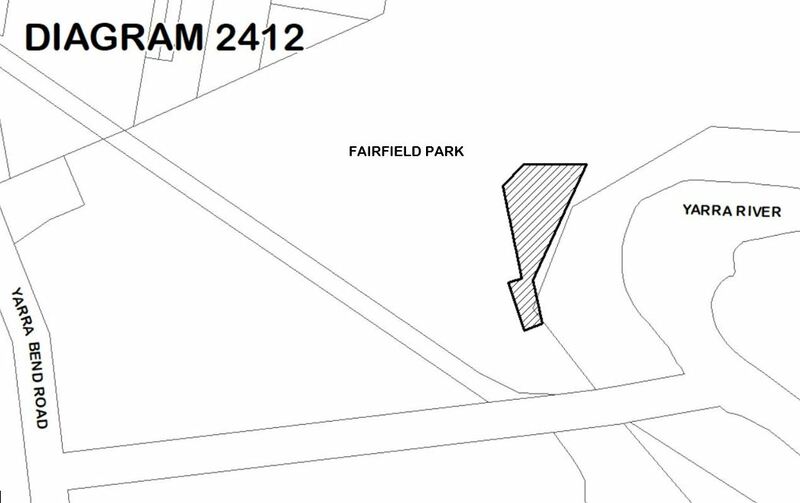

3 FAIRFIELD PARK DRIVE FAIRFIELD, YARRA CITY

FAIRFIELD PARK AMPHITHEATRE COMPLEX

3 FAIRFIELD PARK DRIVE FAIRFIELD, YARRA CITY

All information on this page is maintained by Heritage Victoria.

Click below for their website and contact details.

Victorian Heritage Register

-

Add to tour

You must log in to do that.

-

Share

-

Shortlist place

You must log in to do that.

- Download report

Fairfield Amphitheatre

On this page:

Statement of Significance

What is significant?

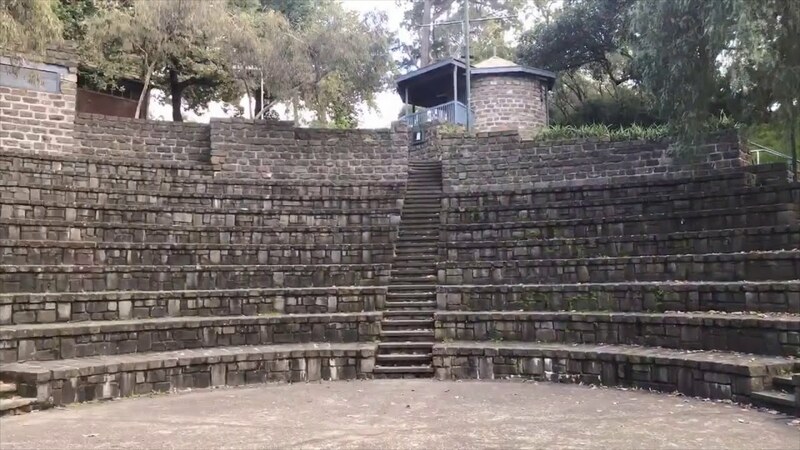

Fairfield Park Amphitheatre Complex including the bluestone amphitheatre designed by Maggie Edmond (1985), precast concrete pavilion designed by Paul Couch (c.1987-88) of Carter Couch Architects, and bluestone ticket kiosk (unknown designer post-1985) constructed for the Greek/English bilingual theatre program of the Epidavros Summer Festival.

How is it significant?

Fairfield Park Amphitheatre Complex is of historical significance to the State of Victoria. It satisfies the following criterion for inclusion in the Victorian Heritage Register:

Criterion A

Importance to the course, or pattern, of Victoria's cultural history.

Why is it significant?

Fairfield Park Amphitheatre Complex is historically significant for its representation of the bicultural importance of Greek-Australians in Victoria’s social, cultural and political development. It represents a significant moment in the migration continuum between the inception of Australia’s postwar immigration program from Greece in 1947, the Federal government’s policy of multiculturalism from the late 1970s, and decline of Greek migration at the end of the 1980s, by which time around 96 per cent of Victoria’s Greek community lived in Melbourne. Modelled on the ancient amphitheatre at Epidavros (late 4th century BC), the cultural importance of the Fairfield complex in Melbourne’s migrant cityscape transcended its immediate suburban scale, and became an important expression of identity for Greek-Australians across Victoria.

Show more

Show less

-

-

FAIRFIELD PARK AMPHITHEATRE COMPLEX - History

Amphitheatres

Amphitheatres can be traced to Ancient Greece (˜800 BC to 146AD). They are circular or oval shaped venues for theatre and outdoor entertainment (semi-circular forms were originally known as ‘theatres’). The amphitheatre form has been adopted by subsequent civilisations especially those aspiring to reflect a glorious classical past. In modern parlance, an amphitheatre is any circular, semicircular or curved, acoustically vibrant performance space, including those with theatre-style stages, sloping seating, particularly those located outdoors. Natural formations of similar shape are sometimes known as natural amphitheatres. The Ancient Theatre of Epidavros (late 4th century BC) which seats 15,000 people is regarded as the best-preserved ancient amphitheatre in Greece due to its outstanding acoustics and fine structure.

Outdoor theatre

Outdoor theatre has a long history across all cultures dating back to the Ancient world and beyond. In the early British and European worlds, travelling performance troupes set up temporary stages in city squares, and from the 15th century some cities, including York and Chester, had identifiable outdoor theatre spaces. Population increases in cities encouraged the building of permanent outdoor and indoor theatres from the 17th century. In Victoria, travelling circus shows were popular in Melbourne and the gold field areas from the 1850s, taking place in tents and other temporary structures. As Melbourne and other towns and cities grew, permanent indoor theatres were built. One outdoor performance structure continued in popularity throughout the nineteenth century – the bandstand (or performance rotunda). Substantial and elaborate architectural structures were common to accommodate bands, typified by Australia’s earliest extant bandstand in the Fitzroy Gardens (1864) (part of VHR H1834). Through these structures, local councils displayed their status and allowed the populace to hear live music in the era before radio (1920s/30s). The construction of bandstands became less common from the mid-twentieth century.

From the 1970s, the growth of seasonal outdoor festivals (in good weather) and community theatre has seen municipal governments and entertainment promoters utilise temporary stages rather than invest in permanent outdoor performance venues. ‘Pop up’ structures can be quickly built, are removed easily, require no upkeep costs, and can be in a different place each year. Examples include the Sunbury Music Festival (1972-75), theatre in the Royal Botanical Gardens and rock concerts at wineries in regional Victoria. Large amphitheatre-style sports stadia have also been used for major theatrical and musical performances, such as the Kooyong Tennis Stadium, Princes Park Football Ground and the MCG, due to the large crowd capacity. These were intended for musical, rather than theatrical performance. In the later twentieth century, amphitheatre-style arenas such as the Melbourne Cricket Ground (VHR H1928) and Waverley Park (formerly VFL Park) (VHR H1883) have been used as live music venues because of their large seating capacity.

Origins of Fairfield Park (early 1900s)

The topography of Fairfield Park has made it a natural place for gathering and recreation. Located at a hairpin bend along the Yarra River, the upward sloping riverbanks provide a sheltered place for swimming, boating and socialising. In 1906 the Fairfield Swimming Club commenced meeting there and in 1908 the original single-storey Fairfield Park Boathouse was built. In 1912 Fairfield Park, covering 15 acres, was formally reserved for public purposes and formal landscaping works began. The park was planted out with four hundred young trees sourced from the Mt Macedon Nursery and surrounded by a picket fence with an iron entrance portal. A rotunda was built but removed (dates unknown).

Use of Fairfield Park (1914-1950s)

At its opening in July 1914, Fairfield Park was described as being on ‘one of the most beautiful stretches’ on the Yarra River. The Heidelberg Shire laid out the paths and plantings and Carlo Catani, Chief Engineer of the Public Works Department, designed the tiered rockeries on the hillside facing the river. Catani, a noted engineer, had reportedly desired greater input into the park’s design but this did not eventuate. During the 1920s there was a boom in water-based recreation along the Yarra. In 1925 the Heidelberg Council constructed a swimming pool abutting the river. In 1932, the Fairfield Swimming and Life Saving Clubhouse (Panther Pavilion) was built. Open-air carnivals, sports matches and boating competitions were common sights at Fairfield well into the 1950s.

The Decline and Revival of Fairfield Park (1950s-1980s)

From the 1950s the Yarra River became increasingly polluted; boating became a less popular pastime and the Fairfield riverside swimming pool was closed. The boathouse gradually fell into a state of disrepair and shut in 1980. From the mid-1980s, however, the Northcote Council began to invest in Fairfield Park. The boathouse was substantially reconstructed as a two-storey Edwardian-style building in 1985 to attract visitors to the area. In the early 1980s the Council also launched the Epidavros Summer Festival, including the bilingual theatre program held in the Fairfield Park. Theatre director Helen Madden worked with the local Greek community to stage classical plays on a temporary stage with scaffolded seating set into a natural amphitheatre above the river. The success of the theatre program from 1983 led the Northcote Council to gain Commonwealth funding to build a permanent amphitheatre.

Northcote Amphitheatre (1985-86)

In 1985 the Northcote City Council commissioned Edmond and Corrigan to design a permanent amphitheatre and building commenced. By the 1980s Peter Corrigan was well known within the theatre community having worked as a theatre, set and costume designer in this field since the 1960s. The amphitheatre working group of the Northcote City Council selected Edmond and Corrigan due to this reputation. Helen Madden recalls that Corrigan’s vision was to create a ‘professional venue which fitted into the hillside’. The working group agreed that the amphitheatre should be modelled on the Ancient Greek Epidavros Amphitheatre (late 4th century BC).

Maggie Edmond prepared plans for the amphitheatre using antiquarian drawings sourced from the University of Melbourne Architecture Library. It comprised eleven tiers of terraced seating in a semi-circular arrangement around a circular stage which is ten metres in diameter. The 460-seat bush amphitheatre was, in Edmonds words ‘designed to meet the park’ and fitted into the ‘natural shell’ of the landscape being sympathetic to the environment as well as providing a commanding stage for theatrical productions. During 1985 unemployed people built the theatre through a ‘work for the dole’ scheme. They were trained in stone-cutting skills and used recycled bluestone pitchers from inner city gutters and laneways.

The Kiosk (post-1985)

The conical kiosk to the northwest side of the amphitheatre was not designed by Maggie Edmond, although constructed in a complementary circular style from bluestone and concrete. It was built after the amphitheatre and functioned as a ticket sales booth and refreshments outlet. The designer and date of construction are unknown.

The Pavilion (c.1987-8)

The Pavilion designed by Paul Couch of Carter Couch Architects was built after the amphitheatre to support its theatrical activities. It provided performance change rooms; a theatrical set building workshop; public toilets; and a public barbeque area. It was constructed using a steel frame and a tilt slab technique (pouring concrete panels on-site then the ‘tilting’ them into their final position using a crane). Prior to construction the site was, in Couch’s words ‘a big cliff’ into which the pavilion was ‘pushed’ so that it did not intrude into its natural surroundings. The building employs a minimal palette of materials. Couch reflects that ‘If you could make it invisible, that would be the ultimate … you don’t want to spoil the park’. The pavilion was designed to be a covered in greenery and blend into the landscape by virtue of a foliage covering the whole structure. Only parts of the metal lattice remain. The rooftop barbeque level is partly shaded by a gazebo with a cube-shaped light box on top. The Northcote Council intended to install fixed barbeques and seating in this area, but this did not occur.

Maggie Edmond

Maggie Edmond graduated from the University of Melbourne in 1969 winning several awards for excellence during her studies. She began her career working on large-scale projects in Melbourne and Sydney and in 1974 formed a partnership with Peter Corrigan. Edmond and Corrigan’s first published projects, the Edinburgh Gardens Pavilion (1977) and Patford House (1975) were designs developed solely by Edmond. At Edmond and Corrigan, she managed and presented most office work. At the same time, she designed a significant collection of residential alterations and additions under her own name. Edmond and Corrigan’s work is associated with the emergence of architectural postmodernism in Australia, and their work in the 1990s and 2000s includes RMIT University’s Building 8 (1990-4) and the Victorian College of the Arts (VCA) Drama School (2002). The firm has won numerous awards. Through her work at Edmond and Corrigan, Edmond became a key part of an internationally significant Australian architectural practice. In 2001, Edmond was awarded a Life Fellowship by the RAIA and in 2008 Neil Clerehan described her as ‘probably the nation's foremost female architects’. In 2015 she was awarded an honorary Doctor of Architecture by the University of Melbourne. The Fairfield Amphitheatre is Edmond’s favourite project because it involved working with the local community within an informal, iterative process. For Edmond it represented a small-scale project, different to the large projects that the Edmond and Corrigan office were involved in during the mid-1980s, such as the Australian Galleries at the NGV and Dandenong TAFE.

Paul Couch

Paul Couch [pronounced ‘Cooch’] was born in Melbourne in 1938. In 1959 he joined the firm of Grounds, Romberg and Boyd, one of the most innovative architectural practices in Australia. Couch registered through the Architects Registration Board apprenticeship and examination system around 1970, rather than undertaking a university degree. Under the tutelage of design luminaries Roy Grounds, Frederick Romberg and Robin Boyd, Couch worked on some of the icons of Modernist Australia, including the Academy of Science in Canberra (1958); National Gallery of Victoria (1968) and Ormond College and McCaughey Court (1963). His residential work with Boyd included documenting the Featherston House at Ivanhoe (1967). When Roy Grounds left Grounds, Romberg and Boyd in 1962, Couch remained with Romberg and Boyd (the firm retaining Boyd’s name after his death in 1971) and became a director in the 1980s. In 1983, he formed a partnership with Dennis Carter. Few of Couch’s designs have been published and there is relatively little biographical information available in print.

Concrete construction

The Fairfield Pavilion exemplifies Couch’s preferred style of tilt-slab concrete construction used to great effect in small-scale settings. Couch describes himself as a pragmatic architect. He has designed and built over thirty fire-resistant houses of concrete or Corten steel in Victoria. He has received awards from the Royal Australian Institute of Architects (1987 and 1989) and the Master Builders Association. From the nineteenth century, Victoria was at the forefront in Australia in developing concrete construction techniques. Innovative uses of reinforced concrete are evident in the dome of the State Library of Victoria (1906) (VHR H1497) and the Barwon Ovoid Sewer Aqueduct (1915) (VHR H0895). Throughout the twentieth century concrete continues to be used as a durable and convenient construction material. From the 1950s onwards significant advances in building techniques opened the scope for concrete construction, and Brutalism emerged as an architectural style (from the French 'Beton brut' [raw concrete]). Some notable examples of late twentieth-century concrete construction in the Victorian Heritage Register include the Plumbers and Gasfitters Union Building (VHR H2307), Harold Holt Memorial Swimming Centre (VHR H0069) and Total House (VHR H2329). Paul Couch prefers not to categorise the Fairfield pavilion or his other works under a particular architectural style.

Selected bibliography

‘A Brief Introduction to Bandstands’, Historic England, https://heritagecalling.com/2018/07/06/a-brief-introduction-to-bandstands/ [Accessed, 22 March 2021].

‘Fairfield Park’, Heidelberg News and Greensborough and Diamond Creek Chronicle, 4 July 1914, p.3.

‘Get to know architect Maggie Edmond of Edmond and Corrigan’ The Real Estate Conversation https://www.therealestateconversation.com.au/profiles/2017/11/16/get-know-architect-maggie-edmond-edmond-and-corrigan/1510776325 [Accessed 8 February 2021].

‘High Diving at Fairfield’, Argus, 4 Feb 1924, p.7.

‘Open Air Theatre’, The Australian Jewish News, 21 Mar 1986, p.24.

‘Proposed demolition of River Pavilion in Fairfield Park sparks heritage campaign’, National Trust Advocate (9 October 2020) https://www.trustadvocate.org.au/proposed-demolition-of-river-pavilion-in-fairfield-park-sparks-community-heritage-concerns/ [Accessed 8 February 2021]

‘Stork Theatre – Beginnings’, https://www.storktheatre.com.au/history/ [Accessed 8 February 2021].

‘The unofficial history of the Fairfield Boathouse’, Interviews with Rafael Epstein, ABC Radio Melbourne Drive, https://www.abc.net.au/radio/melbourne/programs/drive/unofficial-history-of-fairfield-boathouse/11522048.

ACT Heritage Council, Background Information Open Systems House (Former Churchill House), April 2018, https://www.environment.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/1186409/BI-Open-Systems-House.pdf [Accessed 14 April 2021].

Allom Lovell & Associates and John Patrick Pty Ltd, City of Yarra, Heritage Review Landscape Citations, July 1998

Darebin Heritage, ‘Northcote Amphitheatre’, https://heritage.darebinlibraries.vic.gov.au/article/61, [Accessed 4 March 2021].

Goad, Philip and Julie Willis, Encyclopedia of Australian Architecture, Cambridge University Press, November 2011.

Hamann, Conrad with Michael Anderson and Winsome Callister, Cities of Hope: Australian Architecture and Design by Edmond and Corrigan, Oxford University Press, Melbourne 1993.

Hamann, Conrad, Cities of Hope: Remembered/Rehearsed, Thames & Hudson, 2012.

Heritage Council of Victoria & Aboriginal Heritage Council of Victoria, Victoria’s Framework of Historic Themes, 2010.

Heritage Council Registrations and Reviews, Committee, VHR Determination, Preston Market, 18 September 2019.

'Historic open-air theatre still creating excitement for outback audiences', ABC News Online, 20 June 2014 https://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-06-20/historic-open-air-theatre-still-creating/5538092 [Accessed 10 March 2021].

Interview with Helen Madden, 19 April 2021.

Interview with Maggie Edmond, 19 March 2021.

Interview with Paul Couch, 24 February 2021.

Mark St Leon, ‘Circus’, in eMelbourne: The City Past and Present [Accessed: 22 March 2021].

VCAT Determination, Nolan v Yarra CC [2020] VCAT 842 (14 August 2020).

FAIRFIELD PARK AMPHITHEATRE COMPLEX - Assessment Against Criteria

Criterion

Fairfield Park Amphitheatre Complex is of historical significance to the State of Victoria. It satisfies the following criterion for inclusion in the Victorian Heritage Register:

Criterion A

Importance to the course, or pattern, of Victoria's cultural history.Why is it significant?Fairfield Park Amphitheatre Complex is historically significant for its representation of the bicultural importance of Greek-Australians in Victoria’s social, cultural and political development. It represents a significant moment in the migration continuum between the inception of Australia’s postwar immigration program from Greece in 1947, the Federal government’s policy of multiculturalism from the late 1970s, and decline of Greek migration at the end of the 1980s, by which time around 96 per cent of Victoria’s Greek community lived in Melbourne. Modelled on the ancient amphitheatre at Epidavros (late 4th century BC), the cultural importance of the Fairfield complex in Melbourne’s migrant cityscape transcended its immediate suburban scale, and became an important expression of identity for Greek-Australians across Victoria. [Criterion A]

FAIRFIELD PARK AMPHITHEATRE COMPLEX - Permit Exemptions

General Exemptions:General exemptions apply to all places and objects included in the Victorian Heritage Register (VHR). General exemptions have been designed to allow everyday activities, maintenance and changes to your property, which don’t harm its cultural heritage significance, to proceed without the need to obtain approvals under the Heritage Act 2017.Places of worship: In some circumstances, you can alter a place of worship to accommodate religious practices without a permit, but you must notify the Executive Director of Heritage Victoria before you start the works or activities at least 20 business days before the works or activities are to commence.Subdivision/consolidation: Permit exemptions exist for some subdivisions and consolidations. If the subdivision or consolidation is in accordance with a planning permit granted under Part 4 of the Planning and Environment Act 1987 and the application for the planning permit was referred to the Executive Director of Heritage Victoria as a determining referral authority, a permit is not required.Specific exemptions may also apply to your registered place or object. If applicable, these are listed below. Specific exemptions are tailored to the conservation and management needs of an individual registered place or object and set out works and activities that are exempt from the requirements of a permit. Specific exemptions prevail if they conflict with general exemptions. Find out more about heritage permit exemptions here.Specific Exemptions:General

• Minor repairs and maintenance which replaces like with like. Repairs and maintenance must maximise protection and retention of fabric and include the conservation of existing details or elements. Any repairs and maintenance must not exacerbate the decay of fabric due to chemical incompatibility of new materials, obscure fabric or limit access to such fabric for future maintenance.

• Maintenance, repair and replacement of existing external services such as plumbing, electrical cabling, surveillance systems, pipes or fire services which does not involve changes in location or scale, or additional trenching.

• Works or activities, including emergency stabilisation, necessary to secure safety in an emergency where a structure or part of a structure has been irreparably damaged or destabilised and poses a safety risk to its users or the public. The Executive Director, Heritage Victoria, must be notified within seven days of the commencement of these works or activities.

• Painting of previously painted external and internal surfaces in the same colour, finish and product type provided that preparation or painting does not remove all evidence of earlier paint finishes or schemes. Note: This exemption does not apply to areas where there are specialist paint techniques such as graining, marbling, stencilling, hand-painting or signwriting, or to wallpapered surfaces, or to unpainted, oiled or varnished surfaces.

• Cleaning including the removal of surface deposits by the use of low-pressure water (to maximum of 300 psi at the surface being cleaned) and neutral detergents and mild brushing and scrubbing with plastic not wire brushes.Temporary Events

• The installation and/or erection of temporary elements associated with short-term events for a maximum period of three days' duration after which time they must be removed and any affected areas of the place made good to match the condition of the place prior to installation. These elements include:- Temporary structures such as shelters, marquees and tents (lightweight structures) which are weighted down with sandbags or water tanks and avoid the requirement for driven metal stakes which could impact on tree roots. Where pegging is not able to be avoided this is to be located to avoid tree roots (i.e. not driven into if encountered).

- Marquees, tents, stages, seating and the like which are located no closer than three metres from the base of a tree.

- Temporary security fencing, scaffolding, hoardings or surveillance systems to prevent unauthorised access or secure public safety.

- Temporary structures, vendor and toilet vans which are located on existing hardstand and paved/asphalted areas and pathways or on turf areas with a protective surface (board or track mats).

- Temporary infrastructure, including wayfinding/directional signage, lighting, public address systems, furniture and the like in support of events which do not require fixing into the ground.

Interiors (Kiosk and Pavilion)• Installation, removal or replacement of existing electrical wiring. If wiring is currently exposed, it should remain exposed. If it is fully concealed it should remain fully concealed.

• Removal or replacement of light switches or power outlets.

• Maintenance, repair and replacement of light fixtures, tracks and the like in existing locations.

• Maintenance and repair of light fixtures, tracks and the like.

• Removal or replacement of smoke and fire detectors, alarms and the like, of the same size and in existing locations.Landscape/Outdoor AreasHard landscaping and services

• Subsurface works to existing watering and drainage systems provided these are outside the canopy edge of trees and do not involve additional trenching. Existing lawns, gardens and hard landscaping, including gravel footpaths and forecourt are to be returned to the original configuration and appearance on completion of works.

• Maintenance, repair and replacement of existing above surface services such as plumbing, electrical cabling, surveillance systems, pipes or fire services which does not involve changes in location or scale.

• Repair and maintenance of the existing gravel footpaths and forecourt where fabric, design, scale and form is repaired or replaced, like for like.

• Installation of physical barriers or traps to enable vegetation protection and management of small vermin such as rats, mice and possums.

Gardening, trees and plants

• The processes of gardening including mowing, pruning, mulching, fertilising, removal of dead or diseased plants (excluding trees), disease and weed control and maintenance to care for existing plants.

• Removal of tree seedlings and suckers without the use of herbicides.

• Management and maintenance of trees including formative and remedial pruning, removal of deadwood and pest and disease control.

• Emergency tree works to maintain public safety provided the Executive Director, Heritage Victoria is notified within seven days of the removal or works occurring.

• Removal of noxious weeds.

-

-

-

-

-

FAIRFIELD HOSPITAL (FORMER)

Victorian Heritage Register H1878

Victorian Heritage Register H1878 -

FORMER COLLINGWOOD TIP

Victorian Heritage Inventory

Victorian Heritage Inventory -

GRANDVIEW HOTEL

Victorian Heritage Inventory

Victorian Heritage Inventory

-

1 SPRING STREET (SHELL HOUSE)

Victorian Heritage Register H2365

Victorian Heritage Register H2365 -

5 Circle Place

Yarra City

Yarra City

-

-